Submarine Intrusions in Swedish Waters During the 1980s

by

Bengt Gustafsson

About the Author: Born 1933. After beeing recruited 1959 as an Engineer Corps Officer Gustafsson became a General Staff Officer and served as a Battaljon Commander in the Infantry and Commander of an Engineer Regement. He was Head of Planning and Budget in the Ministry of Defence

1982-84, Commander of Upper Norrland Military District 1984-86 and Supreme Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces 1986-94.

This PHP E-Dossier is based on the new book by Bengt Gustafsson entitled 'Sanningen om ubåtsfrågan - Ett försök till analys', 2010. For further details click here.

The Truth is in the Eye of the Beholder

Conspiracy theories, alternative explanations, and urban legends frequently play important roles in shaping public perceptions of high-profile events in history. Such alternative views are sometimes based on ideological preconceptions, the failure to appreciate the complexity of issues, or specific preconceptions about individuals, occupations, or institutions. In Sweden, the reception of what is known as ‘the submarine issue’ is a prominent example of such dynamics. The Swedish armed forces assert that from the middle of the 1970s until autumn 1992, foreign submarines repeatedly conducted intrusions far into Swedish territorial waters, including in the direction of the country’s naval bases. There was only one occasion on which the nation responsible for the incursion was successfully identified – when a Soviet Whiskey class submarine was discovered to have run aground in a bay just east of Karlskrona Naval Base in southern Sweden and was found on the morning of 28 October 1981. Journalists covered the event under headlines such as ‘Whiskey on the Rocks’. In Sweden, this event is known as the ‘U-137-incidenten’ [‘U-137 Incident’] after the temporary designation given to submarine S-363 by the Soviet Union for the operation.

In September of the previous year, the last Swedish destroyer in service, HMS Halland, had been deployed against a pair of submarines that were discovered in the outer Stockholm archipelago. One of them headed out towards international waters when it noticed that it had been detected, although it did not come up to the surface so that its nationality could be determined, as required under regulations concerning the admission of foreign naval vessels to Swedish waters. The other one remained in Swedish waters and began a cat-and-mouse game with the helicopters and destroyer that were deployed. In so doing, it demonstrated a maneuverability not previously witnessed. A few depth charges were dropped, but without any visible results.

In the autumn of 1982, the alarm was once more raised about suspected submarines off the Stockholm archipelago. This time, weapons were repeatedly deployed against indications of foreign underwater activity. This anti-submarine operation came to be christened the ‘Hårsfjärden Incident’ after the place where some of these indications were detected. The Swedish Navy’s Berga Navy School was situated at Hårsfjärden. This allowed the international press to follow the anti-submarine operations at close quarters. However, on this occasion, too, the weapons deployed failed to force the underwater craft to the surface, as the Swedish Navy had been ordered to do. During later incidents, the order was changed to sink the underwater craft. An extensive investigation of the seabed followed, during which tracks from caterpillar treads were found at several different places, indicating that small craft had been involved in the unknown vessels’ operations. It was estimated that, in total, a handful of submarines were involved in this event, one of which served as a so-called mother submarine to the smaller vessels. Subsequently, the Swedish Navy began to review earlier reports of suspected submarine violations and discovered that violations of this new type had probably begun in the middle of the 1970s. Among other things, a mine had been removed from a permanent minefield in the vicinity of a naval base at Sundsvall in central Norrland.

Furthermore, the 1983 Submarine Defense Commission, chaired by the former Social Democratic defense and foreign minister, Sven Andersson, was appointed to examine what had happened and given the task of proposing measures for strengthening Sweden’s capacity to protect itself against these violations. Among the commission members was Carl Bildt, who was then the foreign policy spokesman for the Moderate Party.[1] Following a press conference on 26 April, the commission submitted a report to the government entitled “SOU 1983: 13: Att möta ubåtshotet” [“Countering the Submarine Threat”].[2]

The commission believed that existing indications pointed to the Soviet Union as responsible for the violations, with the possible aims of intelligence collection and/or training exercises. The report led to the Palme government immediately presenting a note to the Soviet ambassador in Stockholm, explaining that the government had no information to contradict the conclusions of the commission. The wording of the letter allowed the Politburo to claim that it had no knowledge of such military operations. Predictably, the Soviet Union rejected the allegation, especially as it had previously officially explained U-137’s appearance in the Blekinge archipelago as the result of defective navigational aids.

Even before the inquiries of the 1983 commission, a rumor began to circulate about the Hårsfjärden incident, citing in particular a later event that took place further south, where a permanent minefield was located close to the island of Mälsten. In March 1983, a Swedish business publication, Dagens Industri, published an article alleging that a West German submarine was intentionally released from Mälsten, where it was being held. Journalists, authors, and politicians – generally with strong left-wing sympathies – gradually began to question whether submarine violations apart from U-137 had taken place. They began to speak of ‘budget submarines’.[3] Doubts grew after another incident in the winter of 1984, this time at Karlskrona Naval Base. Once again, the deployment of weapons produced no visible results. "If foreign submarines were in Swedish waters, why were none of them sunk? Surely, the Swedish Navy wasn’t that inept?," was a question being asked.

In the summer of 1984, the supreme commander of the Swedish armed forces, Lennart Ljung, first mentioned in his diary the rumor that it was American – and not Soviet – submarines that were involved at Hårsfjärden, and that a damaged American submarine had been towed out through the Sound shortly after the 1982 incident. The Soviet Union, whose propaganda had initially concentrated on U-137’s purported navigational error, promptly took advantage of the emerging rumor and urged Sweden to sink the American submarines. The Soviet disinformation campaign continued through the early 1990s.

A Split on the Domestic Front

When taking office for his second term – which coincidentally took place during the Hårsfjärden incident – Prime Minister Olof Palme appointed Lennart Bodström as foreign minister in his government. Bodström, previously a trade union chairman, was rather inexperienced in foreign policy, leaving Palme, no doubt, with the most important aspects of foreign policy. In 1985, Bodström attended a dinner arranged by Swedish journalists at one of Sweden’s largest daily newspapers, the liberal Dagens Nyheter. The journalists represented several different right-wing newspapers. According to the journalists, during a question-and-answer session, Bodström made it clear that he “did not believe we had any submarine incursions, and if we did, they were not Soviet ones.”[4] When Bodström’s opinion was made public in newspapers, the center-right party leaders in the Swedish Parliament demanded the foreign minister’s resignation. Palme, however, defended Bodström at least through that autumn’s election, and, after a short period as minister of education, he was appointed ambassador to neighboring Norway.

In defending Bodström, Palme went on the offensive, accusing the opposition of breaching the agreed security policy. Palme persisted in his criticism despite all party leaders stating their support of the government’s declared foreign policy. He therefore succeeded in redirecting the focus of the news debate to the policy of neutrality instead of Bodström’s statements. Along with earlier politically contentious issues connected to the submarine issue, Palme created a political split on the submarine issue, in which the armed forces became involved. This must have surprised the outside world, as typically a major ordeal, which these incursions were for an officially neutral state, lead to a sense of national unity, such as that which existed at the beginning of his second term when Palme appointed the 1983 parliamentary commission.[5] He also publicly and loudly criticized Carl Bildt for straining the policy of neutrality by immediately traveling to Washington after the commission’s press conference. This was an unnecessary attack, which others in the party’s leadership perhaps regretted, since Olof Palme’s outburst resulted in Bildt becoming better known to the public. In fact, when the center-right parties won the 1991 election, Bildt became prime minister for a short time.

In the autumn of 1994, however, the Social Democrats returned to power and Olof Palme’s successor as party leader and prime minister, Ingvar Carlsson, soon set up an expert commission to clarify what happened during the submarine incursions of the 1980s.[6] The 1995 Submarine Commission was to examine in detail evidence submitted by the armed forces in the case of ten alleged violations. The commission came to the conclusion that it agreed with the supreme commander’s verdict that Sweden had experienced several deep incursions by submarines, including at naval bases, and that U-137’s incursion was intentional. While the commission backed up most of what the armed forces had stated, it said that it was not qualified to ascertain which nation was responsible for the deep incursions.[7] In practice, it was rejecting the determination of nationality by the first commission, chaired by Sven Andersson.

Thus, a year later, an internal inquiry was set up at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the findings of which were regrettably classified as top secret in the autumn of 1996. According to media leaks, the committee heading up the inquiry concluded that the Soviet Union was likely responsible for the violations, although the possibility of violations by another country could not be ruled out. It was unfortunate that this was classified as top secret; in hindsight, there was never a more appropriate time for the government’s official position. Publication of its findings would have made its later actions in this matter easier. Future admission or any access to sources within this area seems unlikely; as such, analysis can be carried out only on the basis of indications and evidence currently available.

Meanwhile in Norway, Bodström met Norwegians who, like him, questioned the very existence of these violations. In the case of Sweden, the talking about Soviet submarines seemed politically counterproductive, pushing public opinion and thereby the neutral Palme government right into the hands of NATO. On his return to Sweden as a retiree, Bodström became one of the founders of the self-appointed ‘Citizens’ Commission’, which claimed that apart from U-137, which according to them entered Swedish waters due to navigational problems, no other foreign submarines had entered Swedish waters. The group also included a coast artillery officer who, like the naval officer who conducted the interrogation of the crew of the U-137, distanced himself from the theory that the tracks found on the seabed could have been caused by underwater craft. Both stated that these were more likely to have resulted from anchors being dragged, which will be addressed later. Henceforth, people and groups with this attitude will be referred to as ‘skeptics’.

Unlike almost any other country that was violated by submarines, both the armed forces and the government in Sweden held frequent press conferences about these incidents. This openness was likely a result of U-137 and all the weapons deployed in connection with the Hårsfjärden incident. Norway was also forced to go public about its violations, after Norwegian journalists were alerted to anti-submarine operations that deployed weapons. In Sweden, this was formalized through the government periodically commissioning descriptive and evaluative reports from the armed forces. Of particular interest was the government and armed forces’ response to incursions. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Swedish Navy – or, in any case, its naval officers – was of course also interested in the violations being brought to the attention of the general public and politicians, since in terms of budget the navy was getting squeezed between an increasingly more expensive air force and a large army based on compulsory military service. This interest waned, however, when groups began to question the navy’s competence, as it did not obtain any visible results from its anti-submarine operations. This situation also led to an increase in the number of skeptics among journalists and politicians, especially those on the Left.

In the spring of 1992, Christer Larsson, a radio reporter, revealed that during the Cold War the armed forces had maintained certain technical preparations, enabling it to receive assistance from NATO in the event of a Soviet attack. On the political side, knowledge of the substance of these preparations had been limited to the prime minister and the minister and state secretary at the Ministry of Defence; on the military side, to a handful of generals/admirals in the high command with a few officials for assistance and, in any case, up until the 1960s, also a few regional commanders.

In short, the parliamentary Advisory Council on Foreign Affairs was informed that on 9 February 1949 the government was to make a decision on whether to enter into such cooperation with Denmark and Norway. These preparations will be addressed further under the heading ‘Cooperation with the West’. Carl Bildt, who was prime minister at the time of this revelation, appointed a commission to clarify what these preparations entailed.[9] As is evident by the title of the report, Bildt agreed with the then opposition leader Ingvar Carlsson to only investigate the period up to 1969, meaning neither of Olof Palme’s periods in government would be subject to investigation (the first half of the 1970s and the middle of the 1980s). It would soon prove to be the case that the public was not satisfied with this, and Göran Persson, the Social Democratic prime minister who followed Carlsson, decided to have the submarine inquiries and the Commission on Neutrality Policy (NPK) supplemented. To that end, he appointed a single investigator, Rolf Ekéus, the newly returned ambassador from Washington. Despite other onerous tasks, the latter was to complete two reports within a period of two years.[10]

However, Ekéus did not put the nationality question to bed either. On the contrary, he increased confusion by saying in the report that he did not need to decide whether U-137’s intrusion was intentional or unintentional. Immediately after the report was published, he did, however, express the fact that he personally supported the Soviet explanation of a navigational error. His conclusion on the issue of nationality is as follows:

The majority of reasons thus suggest that the motives behind the underwater violations were for the function of operational planning prior to a great power conflict in Central Europe and that, therefore, both pacts could have had similar reasons for being interested in violating Swedish waters. The Soviet Union can, therefore, hardly be ruled out as a possible violating power.[11]

As “both pacts could have had similar reasons” and the Soviet Union “cannot be ruled out”, the reader is undeniably given the impression that Ekéus may just as well believe that it was American or NATO submarines in Swedish waters. Although in that case, this would have been with Swedish permission, as Ekéus refers to Swedish cooperation with the West in the same paragraph.

This is as far as Ekéus dares to go in his public report as regards expressing an opinion on the question of nationality, despite the fact that Ingvar Carlsson went further in his memoirs the year before when he wrote: “The Warsaw Pact had the strongest motives for exploring our waters. This could be a matter of military planning, of intelligence activity, or training and exercise programs. On the information available, it is impossible to rule out NATO submarines having violated our waters at some point.”[12] This is a conclusion that I previously supported on my part, but which I have now re-examined as a result of increasing questions over the last few years. In some circles, it is now asserted that it was mostly NATO submarines that were involved, US submarines in particular. This interpretation has spread throughout the academic world and has acquired more and more advocates among journalists, leading to an increase in the number of skeptics.

The driving force behind this hypothesis about American submarines is a Swedish researcher, Ola Tunander, from the Peace Research Institute in Oslo (PRIO). Initially one of the Submarine Inquiry’s experts, Tunander published books on the topic during the time of the inquiry and later in Sweden and abroad.[13] His 2007 publication, which concentrated on the aforementioned Hårsfjärden incident, was accepted as Working Report no. 16 of the research program Sverige under det kalla kriget (SUKK) [Sweden during the Cold War], despite Tunander’s questionable scholarship, which was seemingly overlooked.

Tunander’s hypothesis is that the Reagan administration, supported by Britain’s Margaret Thatcher, exploited the Soviet submarine running aground in Gåsefjärden to trick the Swedish people into believing that the Soviet Union was continuing to violate Sweden in a provocative manner. The American reason for showing that there were supposedly Soviet submarines along the Swedish coast was so that an increasingly anti-Soviet electorate would force Palme to pursue more pro-Western policies. This is in line with how public perception of an increasing Soviet threat developed and the fact that Carl Bildt, who presented himself as one of the navy’s defenders, was able to take over the government in 1991 from the Social Democrats, who were unclear about the submarine issue. This did lend credibility to Tunander’s theory. His theory also accuses a number of Swedish admirals of being aware of American presence in Swedish waters, and in 1982 even helping an American submarine that was damaged at Hårsfjärden to escape from Mälsten in Stockholm’s southern archipelago, where it was penned in. The admirals would thus have been conspiring against the Swedish government. Tunander goes as far as speculating that naval officers, along with members of the Swedish security service, might have been behind the 1986 assassination of Olof Palme.

In 2000, Jonas Olsson, a reporter for Sveriges Television (SVT), interviewed both the former US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger (1981-1987) and Sir Keith Speed, the British under-secretary of state for the Royal Navy (1979-1981). [14] Tunander attempted to use these interviews to back up his assertions in various ways. Details of these interviews is discussed under the heading ‘Were these NATO Submarines?’ In the autumn of 2007, SVT aired a couple of new programs that used Tunander’s conspiracy theory as a starting point, which encouraged me to once again devote myself to finding better answers to these ever-present questions. In the middle of this work, the secretary of the Submarine Inquiry published a book of his own that supported Tunander and served to further encourage me.[15] Along with Ekéus’s refusal to express an opinion in 2000, this book indicates that the Submarine Inquiry was also questioning whether it was primarily NATO submarines that were involved.

The following account attempts, as far as possible based on the information available, to answer the three questions that are still being discussed, namely:

• Were there actually ever any submarine incursions?

• If so, which party or parties were involved here?

• Was U-137’s intrusion in Gåsefjärden intentional or unintentional?

I do not expect to convince all the skeptics or conspiracy theorists that I have the correct or complete answers, but I hope to encourage political scientists and/or historians to continue to examine this topic and that this essay will provide a gateway to their advanced studies.

The fact that the Swedish armed forces were not able to sink, find, or salvage a submarine, or even force one to the surface so that its provenance could be determined, is the primary reason for talk of budget submarines and the emergence of skeptics. But it is difficult for anyone who has not been involved in anti-submarine operations to understand how hard this is. At the beginning of the 1980s, when Sweden began to realize the significance of these incursions, , the last Swedish destroyer, which along with our frigates had been the main means of anti-submarine operations, was being taken out of service. In the future this task would be dealt with primarily by land-based helicopters, which had a limited weapons load and endurance in the theatre of operations. It took a while before the Swedish armed forces were able to develop its capacity again, primarily due to stagnating training and technology in anti-submarine vessels since the 1960s. Initially, Swedish submarines were used only for surveillance and intelligence activities, and shortly after two of the most modern and best-trained submarines were granted permission to fire, these particular intrusions came to an end.

The armed forces did make an unfortunate miscalculation with regards to the submission of evidence. In those cases where audio from passive sonars was recorded, many sounds that are natural and have a biological origin were observed. Despite this, the authorities involved in the evaluation – the naval staff, the Defence Materiel Administration, and the Swedish Defence Research Agency – made a mistake when they procured a new hydrophone buoy system that was considerably more sensitive than the previous system. In 1992, this system recorded fewer than ten indications of sound; in 1993, just over ten. These were deemed to be propeller cavitations, which, along with parallel events, led to the supreme commander reporting some of them as confirmed submarine incursions. Once the Cold War had ended, the armed forces gradually began to suspect that these sounds could, nevertheless, be biological in origin, particularly as the number of indications increased again in the spring of 1994. For example, at the end of July that same year, the Swedish Navy, by chance, established that the sound of swimming minks, which are rather common in Sweden’s archipelagos, bear a strong similarity to some of the recorded sounds. In light of this, evidence from passive hydrophones carries very little credibility with the Swedish public.

Therefore even if we have an audio library of submarines operating in the Baltic, I will not be referring to these findings in this account in regards to either the incursions or determining responsibility. Other evidence of violations has been reported not only by the armed forces, but also by the 1995 Submarine Commission. These include thefts from and damage to permanent minefields and an anti-submarine net; these were examined by the National Swedish Laboratory of Forensic Science shortly after the damage. This evidence also includes seabed tracks from crafts that on a few occasions were in the bays, such as keels and caterpillar treads, i.e. parallel tracks with a grooved pattern. Skeptics claim that these tracks were caused by different types of anchors being dragged, but the civilian specialists responsible for the investigations have demonstrated clear differences between the tracks we are referring to and those from various types of anchors. In addition, they have been able to compare the tracks from caterpillar treads with tracks from an unmanned experimental vehicle with a caterpillar tread that the Swedish armed forces themselves designed. Three sonar diagrams of recordings taken from active hydrophones in 1984, 1988, and 1992 contain images of a small coastal submarine and another submarine with a length of just under 30 meters with a conning tower. The 1995 Submarine Commission, which carried out a detailed examination of these intrusions, established in several cases that “it has been demonstrated beyond doubt that Swedish territorial waters have been violated on these occasions by foreign underwater craft.”[16] As the investigation was carried out sometime after the incidents, it did not consider itself able to examine individual observations of foreign submarine activity, but in summing up, said:

We believe, however, that the observations by people – particularly in light of the tracks found and the technical indications – lend support to the conclusion that there has been foreign underwater activity in Swedish waters. [17]

The chairman of the commission, Professor Hans G. Forsberg, who at the time also was the president of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences,, participated in a seminar on 30 January 2008 at the Swedish National Defence College, where as part of the discussion, he stated: “However, that there was a considerable number of violations, not just the ten we analyzed in detail, but many more than that, the commission was absolutely convinced of this.”[18] Which party or parties, then, were behind these violations?

Were these NATO Submarines?Both the naval officers who took part in anti-submarine operations, and the submarine officers themselves, including sonar operators in cooperating countries who listened to the tape recordings, believe that ‘if the surface was clear’ Sweden has unambiguous proof of who was behind the incursions. For the reasons given above, however, passive sonar sound evidence will not be used in the subsequent presentation.

It is strange that of all the NATO countries, Tunander and others have chosen to single out the US as the intruder when for many reasons it is the least likely. When the US commenced construction of nuclear-powered submarines in the 1950s it stopped building the diesel-electric variety. This decision was linked to the distance from enemies, necessitating submarines with high speeds and long endurance for operations on the other side of the Atlantic or Pacific. An ocean-going navy, or ‘blue-water navy’, was developed. The only trace I have found of American submarines in the Baltic Sea is from 1955 in the diary of Stig Hansson Ericsson, commander-in-chief of the Swedish Navy. Ericsson notes that the US was joining a procedure the Nordic countries had for keeping track of each other’s submarines at the entrances to the Baltic, on a level with Jutland to beyond the Danish island of Bornholm. Along with Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, the UK had also signed up to this earlier. West Germany would join in the 1960s, once it acquired a submarine force. In the actual straits, all submarines were to surface on both the Danish and Swedish sides, as the straits are heavily trafficked and are so shallow that for safety reasons ordinary submarines must operate visibly. Danish admirals have provided official assurance that these technical checks were carried out.[19] It is notable that to date no witnesses have come forward who can claim to have seen an American submarine in the Öresund Sound, let alone a damaged one being towed.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the US quite simply did not have suitable submarines for operations in the Baltic, or, in any case, not a sufficient number of them in the Atlantic. In addition, it could rely on two of its most loyal European allies, the UK and West Germany, who had a sufficient number of submarines and experience in the region to take, along with Denmark, operational responsibility for the Baltic in times of peace and war. American submarines did not even pay a single visit to a naval base on the Swedish Baltic coast at any time during the Cold War.

Tunander probably feels that the aforementioned Caspar Weinberger interview supports his view, although the interview does not affirm the presence of American submarines. Weinberger did, however, mention NATO and what he calls tests, i.e. the kind of activity in which the US’ so-called ‘red units’ were involved. Tunander suggests, therefore, that the Red Cell for testing naval bases was deployed during the Hårsfjärden incident to check the Swedish naval base’s defenses. There is one major problem with this supposition: this unit was not organized until two years after the incident. Tunander’s alternative theory is that the SEAL (Sea, Air, and Land) team two was deployed, along with Italian midget submarines. But why use Italian midget submarines when the West Germans had their own and SEAL had been working together with their Kampfschwimmer frogmen since 1976? Nor is it likely that the Swedish Navy would have deployed as many weapons if this had involved a conspiracy that had been agreed by Swedish admirals. Moreover, if the intention was a long-term operation aimed at influencing Swedish policy, as Tunander asserts, it would have required a written presidential directive.[20] No such operation is mentioned in the declassified titles of the National Security Decision Directives (NSDDs), and neither of the two that remain classified corresponds time-wise with U-137 being the inspiration for a psychological operation (PYSOP) aimed at Sweden.

In his interview, Keith Speed speaks unequivocally of British submarines “testing” Sweden’s surveillance systems underwater and of these tests taking place in agreement with Sweden via the British Foreign Office.[21] As far as I have been able to ascertain, these tests were carried out in connection with naval visits approved by the Swedish government. These can hardly be called violations. (Swedish submarines also carried out a similar test on another friendly country’s surveillance system in connection with a naval visit.) The British Oberon class submarines regularly entered the Baltic for intelligence operations, at times in connection with Soviet naval target practice in the southeast, at other times in the north, perhaps to canvass the Golf class submarines, whose nuclear missiles had the range to reach the UK. Returning from the latter, the British would sometimes travel north of Gotland and down into the international channel between the island and the mainland. It is possible that they would have entered Swedish waters during such an excursion, or that they would have headed north in an underwater position through the Åland Sea up to the Gulf of Bothnia, which belonged to the theatre of operations of the Allied Forces Baltic Approaches (BALTAP).[22] British submarines (sometimes an entire unit) made regular naval visits to Sweden, even to Baltic ports south of the Åland Sea.

The same applies to the West German coastal submarine units that sometimes made naval visits to ports along the Norrland coast. For the purpose of war tasks and exercises, the West German submarine commander also took command of the few Danish submarines. The German coast is, like the Baltic, less suitable for basing naval forces. The harbors make it easy for an opponent to lie in wait just outside and wait for ships to set sail. Therefore during both the world wars, the so-called resting position of German submarines was in the Swedish archipelagos. During the Cold War, the West German Navy’s options for locating bases were even more vulnerable, which led to an agreement with the Swedish Navy allowing for West German naval forces to regroup in Swedish waters. There was, therefore, a great deal of West German interest in keeping up to date with Swedish coastal areas, which they did by, among other things, naval visits.

Russia (then later the Soviet Union) and Germany had operated submarines in Swedish waters during both world wars. During the Cold War, both countries would certainly have felt the need to keep an eye on each other’s nearby submarines within the same Swedish waters. As mentioned in the introduction, soon after the Hårsfjärden incident, a rumor circulated that the Swedish Navy had intentionally released a West German submarine. When we now attempt, post-facto, to investigate what happened at Mälsten, it turns out that the documentary material required is missing in many cases. This applies to analysis results from something Tunander calls ‘yellow patches’, which he claims are an American distress signal, a tape recording of a sound that was at the time believed to be an underwater repair, the identification of a metal object found on the sea bottom and recorded on video, and a report that the electrical system at Mälsten was responsible for the interference signals picked up by its tape recorder. In the light of this, it is odd that Tunander has not instead asked whether it could have been a West German submarine spying on the Soviet group and entering Hårsfjärden to see what it was doing and then ending up trapped along with the group. They may have later intercepted or been briefed about the fact that – to take account of the risk to third parties – there was, when it was dark, a weapons-hold status for the minefield at Mälsten.

It was, perhaps, a German submarine such as this that went out late in the evening between 13 and 14 October 1982, as, according to the Submarine Inquiry, there are no details mentioned in the Swedish Defence Staff’s war diary apart from stating that there was frantic activity at Mälsten. It could be the case that this was the kind of experience that meant that West German submarines were subsequently so meticulous that they personally reported to the Swedish Defence Staff that they had entered Swedish waters but were on the way out. If this was the case, the Swedish Navy was doing the political leadership a favor – on both sides. Perhaps they even consulted or informed the Swedish politicians. The Swedish parties had a close relationship with their German counterparts, as they did with the British. They would certainly not have wanted to have them embarrassed as a result of a mistake. Of course, if this was the case, it was a one-off.

The good cooperation between the different political parties in Sweden, the UK, and West Germany makes it unlikely that any of these countries would secretly and intentionally have violated Swedish waters in the archipelago areas or in the vicinity of Swedish naval bases – particularly once Sweden had begun to deploy weapons without warning in its inner waters. If a democratic country had been caught red-handed in the way the Soviet Union was in Gåsefjärden, this would also have had consequences for its domestic politics. The cooperation maintained between the political parties had its military equivalent. It is well known that there was cooperation within the areas of intelligence activity and technological development, particularly with the US in the field of aviation. What is less well known is the extensive training given to senior Swedish officers and specialists, primarily within the Swedish Air Force and Navy. The Commission on Neutrality Policy, like the later Inquiry on Security Policy which looked at the Palme period, tones down the extent and degree of Swedish preparations for receiving assistance from NATO in the event of an attack by the Soviet Union. But were there preparations for joining NATO should tensions accelerate and hostilities break out? It was certainly in the interests of the US and NATO, particularly for Denmark and Norway as neighbors, to have Sweden on board in case of a surprise attack by the Warsaw Pact against the Nordic countries – at least until the time when the US would be able to intervene in Europe. The question of these preparations will be looked at in depth later, but first, how did cooperation begin and why?

Cooperation with the WestAfter the occupation of Norway on 9 April 1940 and prior to its attack on the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany had use of the Swedish rail network and the inshore routes for their sea transport along the east coast. Swedish export of iron ore and ball bearings, which was important to German armaments, also continued for most of the war. This action and the declaration of neutrality have often been criticized, particularly by the US (which itself did not enter the war until directly attacked). The Swedish Social Democratic prime minister, Per Albin Hansson, had decided as early as 1938 to try to spare his people from the horrors of a war. He declared to his parliamentary party: “We are all in agreement that our policies must be based on keeping us on the outside in the event of war. If we are forced to become involved, then it is clear that, as Mr Undén [Östen Undén, a Social Democratic politician] has said, we must ensure that we are on the side of the democratic states.”[23] By this, he meant the other Nordic countries and, above all, the UK.

Cooperation with the West began early with the UK.[24] For example, at the end of 1940, the MFA began to regularly send figures on iron ore exports to Germany. At the same time the Ministry of Defence would send the Swedish Navy’s weekly ice reports, making it possible for the British to calculate when iron ore exports went from Luleå in the Gulf of Bothnia to Narvik in northern Norway. Thus, the British were able to attack the iron ore ships on their way down to the North Sea and the Skagerrak. Later, reports from Sweden’s air reconnaissance would also provide information for more mines laying from the air in the Baltic channels that the Germans were using. When the battleship Bismarck left the Baltic in May 1941, this was brought to the attention of the British in the same way. Carl Petersén, then head of a part Swedish intelligence whose existence was unknown to the public , first established a secret channel via a Norwegian to the British legation in Stockholm. Through this, the British also received intelligence from the Danish resistance movement. This was later formalized into direct intelligence meetings held fortnightly. The British would be given access to the remnants of a prototype of a V2 missile that crashed in southern Sweden and were also allowed to set up a signals intelligence station on southern Öland, targeted at the German research station in Peenemünde.[25]

In the autumn of 1943, Sweden began to train Norwegian and Danish conscripts who had been escaping to Sweden since April 1940. This was organized by Tage Erlander, the academically educated under-secretary of state to the Swedish minister of health and social affairs. (Erlander succeeded Hansson as party leader and prime minister when the latter died in 1946.) These units were called ‘police troops’, out of consideration for the declared policy of neutrality.[26] In reality, however, military training was provided with the aim that these escapees take part in the liberation of their respective homelands, or, at a minimum, disarm surrendering Germans and assume territorial responsibility for liberated areas. The deployment of these police troops was under discussion in late autumn 1944, when Soviet forces began to repel the Germans in northern Norway. This was made possible through an American transport aircraft division deployed at a Swedish airbase at Luleå at Christmas time, which was responsible for supplying the Norwegian units until August 1945. The greatest departure from the declared policy of neutrality was not the concession to Nazi Germany at the beginning of the war, but the fact that, at the end, the government allowed the Allies to fly over southern Sweden en route to bombing German cities and industry. In so doing, the Western air force units avoided the strongest elements of the German air defense, which was built up from the Channel coast up to the north of Denmark. This is said to have involved more than 6,000 aircraft missions with information on emergency landing bases being provided verbally to those planes that returned damaged from Germany.[27] Towards the end of the war, an Allied operation to liberate Norway was discussed, which would have taken a route via Gothenburg. The Swedish Defence Staff had a similar operation planned, simply called, ‘Save Norway’. There was also a ‘Save Denmark’ plan.

In 1945, upon the conclusion of peace, a new Swedish military command took over what was, in practice, an already established cooperation with the West, which would be further cultivated due to the inception of the Cold War. For historical and political reasons, the Swedish military command was fiercely anti-Soviet. Sweden was particularly concerned about the situation in Finland; its relatively strong domestic Communist party had the power to appoint the minister of interior in the Finnish government, which itself was under a great deal of pressure from the Soviet chairman of the Allied Control Commission. Concern increased after the Prague coup of 1948.[28] Sweden’s Social Democratic government of the post-war period certainly tried to establish a better relationship with the Soviet government through a trade agreement, but there was never any doubt that Sweden would also choose the democratic side in this new situation if forced to make a choice. It had already dealt with its revolutionary element in 1917.

Cooperation with the British Navy began with mine sweeping in the Danish straits. Swedish naval officers were sent to the UK for training in, among other things, anti-submarine warfare, which the British Navy had devoted a great deal of time to during the war. The Swedish Air Force learned to use radar and night fighters. Surplus equipment from the UK as well as from the equipment left behind in Europe by the US was bought for all divisions of the Swedish armed forces. Training support was provided alongside the equipment.

At the cessation of hostilities, Soviet armed forces were to the south of Sweden. The internal German border between the East and West was established west of the Sound. That a new race between the great powers for the Baltic outlets in case of war was developing was clear to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden’s military authorities. They began to discuss how to avoid friendly fire and perhaps also cooperate on the defense of the three countries and their outlets. Even before World War II, Norwegian and Swedish air defenses had been coordinated. Politically, the Swedish government was striving for a neutral Scandinavian Defence Union and in late autumn 1948 negotiations on such a union were entered into. These soon broke down, primarily because Norway did not want to relinquish its lifeline to the West and the Swedish government insisted that the defense union must be neutral. Norway and Denmark instead joined the Atlantic alliance. The solution for Sweden was to undergo secret preparations for “being able to receive assistance from the democratic side” in “the event of an as yet undefined security situation.”[29] Knowledge of these preparations was confined to a small political and military circle so as not to jeopardize the Swedish policy of neutrality. During the 1950s, there was a coordinated expansion of the Danish and Swedish defenses of the Öresund strait.[30] The protection of essential sea transports through the Skagerrak was jointly planned between Sweden and Norway and a reserve route for Sweden’s imports via Trondheim in central Norway was established, which was also intended for the supply of aviation fuel. For this reason, the Swedish military command proposed planning for an intervention should the Soviet Union launch an operation against Norway across the Lofoten Islands.[31] It is unclear whether this plan was ever sanctioned, but supposedly such a plan did exist at some point during the 1950s.

For the rigid Östen Undén, it appears as if these preparations only included Denmark and Norway, although, as NATO members, they were controlled militarily by NATO’s operational command. As late as 1959, at a presentation for the whole government, with Undén present, Erlander allowed the Swedish Defence Staff to describe only the preparations with Denmark and Norway, including options for coordinating the air defenses.[32] In actual fact, cooperation regarding tactics and unit production was developed further between, for instance, the British and Swedish navies. Meetings had also been arranged between the Pentagon and the Swedish military command and Erlander personally visited President Truman in 1952. A National Security Council (NSC) document from 1948 in which the US complained about the Swedish policy of neutrality, was to be changed in 1952 to expressing support for the Swedish armed forces regarding technological developments. Intelligence cooperation began to be developed, particularly with regard to signals intelligence. In practice, Sweden was treated as if it was a NATO member.[33]

Olof Palme, who, in 1954, began to work part time for Erlander on foreign and security policy issues, while his colleague, Ingvar Carlsson, devoted himself to domestic policy. In a conversation I had with Palme shortly before his death, in which he mentioned the fact that he had worked with analysts within the armed forces’ intelligence service at the beginning of the 1950s, he called Carlsson and himself “Erlander’s general staff”. At the end of the 1960s, at the same time that he was delivering anti-Vietnam War speeches, Palme told future Supreme Commander Stig Synnergren that while the rhetoric was important for domestic policy reasons, the armed forces should ensure that a good relationship with the US continued. This approach was repeated to the incoming commander of the Swedish Navy, Bengt Lundwall, in 1970.[34] In the other democratic parties, only the members of the Advisory Council on Foreign Affairs were informed, probably more succinctly. Trusted senior MFA officials were briefed at times, including those who worked in the NATO countries concerned. Apart from this, only the minister and the state secretary at the Ministry of Defence were fully briefed on cooperation with the West. Anders Thunborg, later the Swedish ambassador to the United States, was at the time Sven Andersson’s first state secretary who was briefed, and this was not until the end of the 1960s.

Now is probably the time to tell the reader that my predecessor as General and Supreme Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces, Lennart Ljung, chose to destroy the documentation detailing these preparations, along with the personal contacts in the cooperating countries, such as West Germany, the UK, and the US. A link was also to be established with the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE). The only thing that was retained at operational command was a ‘telephone directory’. Whether Ljung did this on his own initiative or was asked to do so by Olof Palme I do not know, because both were dead by the time I realized, in the spring of 1992, that these preparations had existed. I find it hard to understand why my predecessor kept quiet. Because, as has proved to be the case from my studies, the secret preparations continued as before behind my back with trips to Copenhagen and Oslo as well as staff talks in London. Moreover, one might think this would be a strange time to discontinue the planning, as the early 1980s was a period during which there was a great deal of tension between the great power blocs, and even, at times, a high level of readiness among the Soviet nuclear forces.

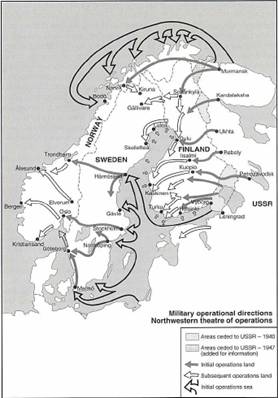

In a recently published article, Mikael Nilsson, a researcher at the National Swedish Defence College, uses declassified NATO sources that have appeared in Norwegian research to describe Operation SNOWCAT (Support of Nuclear Operations with Conventional Attacks). This 1956 plan called for American and British strategic bombers to fly over Sweden on their way to targets in the East Germany, Poland, and the Baltic states, supported by Norwegian fighter aircraft.[35] Even in the 1970s and 1980s, they were to take a low flight path over Sweden. This concurs with how the Soviet Union perceived the threat from Scandinavia (see Fig. 1). There is also the fact that in the 1950s, the Swedish Air Force introduced the NATO standard both for fuel and hose couplings.

Fig. 1. The Soviet view with regard to threats from Scandinavia according to a Russian publication from the 1980s (private archives).

Given Sweden’s importance to NATO’s defense of the Baltic exits and the Northern Flank, it is difficult to imagine that the US or the other NATO countries would politically jeopardize their contact with the Palme government by secretly violating our waters. At the same time as the submarine incursions, the Palme government took part in supporting the independent Polish trade union Solidarity, which of course was not a pro-Soviet stance.[36] In reality, both the US and the UK did what they could to strengthen Sweden’s anti-submarine capacity and bring the violations to an end, for example by equipping Swedish submarines and other vessels with the most modern anti-submarine equipment at their disposal. Rather than disputing cooperation with the West, it is more interesting to understand Erlander, and later Palme’s, motivation.

A Few Reflections

Let me say that I do not think that it was wrong for Sweden to make these practical preparations in order to be able to work together with NATO operationally. If anything, these were not extensive enough to have a sufficient effect. If the aim of Sweden’s security policy was to shape its society in accordance with its values, Sweden should have made it an intention to defend the Nordic countries together with NATO right from the outbreak of war and conducted applicable exercises, at least with Norway. Who believes that we would have had any freedom of action had we become a Soviet satellite within the Warsaw Pact? When in 1992, Christer Larsson revealed the secret preparations, most Swedes probably reacted positively to having prepared for receiving assistance from NATO. In fact had Sweden become involved from the beginning, it could have worked together with the West German, British, and Danish navies and air forces in the Baltic.

However, the fact that Ljung did not inform me of what had taken place – even if he believed that it was being discontinued – is odd. Perhaps Minister of Defence Roine Carlsson believed that Ljung had informed me, because Carlsson himself never raised the matter, despite the fact that I occasionally briefed him about measures I felt were borderline with regards to the declared policy of neutrality. Did he himself not know? My subordinates within the armed forces also did not mention the extent of these preparations. Did they also think that I had been briefed by Ljung? I was involved in intelligence cooperation, but attempted to maintain the bilateral nature of this process. As previously mentioned, the technology and equipment cooperation was also well known, particularly within aviation. In addition, personal relationships were developed, primarily with people in the Nordic countries and in the West, such as with Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) General Jack Galvin. So in this respect, I was personally part of the preparations and was, of course, mentally prepared for it, as it was obvious which side Sweden would choose if forced. But I was fooled by the rhetoric about the policy of neutrality, which became even stronger under Olof Palme. Supposedly, as Lennart Ljung shredding the NATO folder, he said: ‘After all, it is not relevant anymore.’ So, I personally served the purpose of a useful idiot in this double dealing.

As I was not even briefed that we had conducted these preparations with several NATO countries, I have no duty of confidentiality, as a general duty of confidentiality to the government and the armed forces applies only to secrets I was made aware of during my service. Therefore, I feel free to express my views on what I have discovered since my retirement; namely, on our preparations for being able to receive help from NATO as well as perhaps assisting NATO in defending its Northern Flank in Europe in certain situations.

In this section, all that remains are a few reflections. As early as February 1949, Erlander said: “Let us together transform Scandinavia into a fortress so strongly defended, that an attack against us will mean that our territory is transformed into a base area for another, non-aggressive great power grouping.”[37] For its part, the Commission on Neutrality summarizes this as follows:

Against this backdrop, it is clear to the Commission that the Minister of Defence and his closest colleagues were intent that Sweden, with the greatest possible consideration for the policy of neutrality, should make preparations so as to be able – in a threatening, not more closely defined situation – to receive military support from the Western Powers, and that to a certain extent such preparations were actually made in the 1950s.[38]

Is it not conceivable that Erlander came to this conclusion himself? That perhaps in his discussions with Palme, he concluded that Sweden could not stay out of any new great power war and would be forced to take NATO’s side from the outset? Just as in World War II, in the event of a new war the great powers would have needed Swedish airspace and perhaps even use of its airbases. It was, therefore, necessary to involve the major NATO countries in the preparations. As early as 1948, Erlander ordered a study by the armed forces into the basing of American aircraft in Sweden.[39] Preparations for defending Scandinavia along with NATO from the very outset of war were, however, not something that he could win over his party with, or even secretly his government. The ‘policy of neutrality’ was perhaps only for times of peace. It has, of course, been convenient for social democracy to be able to explain this policy by referring to Finland. In reality, the desire to remain in power has been the main incentive. That Per Albin Hansson succeeded in keeping Sweden out of World War II due to a policy of neutrality was a winning phrase during the Cold War, which gradually captivated the Swedish public. This argument continues to the present day in the form of Sweden’s militarily non-alignment, despite it being a member of the European Union and as such a participant in its foreign policy. Hansson was lucky because in reality neutrality is not what saved Sweden; it was Finland, as Göran Persson acknowledged.

As things turned out, the Soviet Union probably knew of Sweden’s cooperation with the West at an early stage, so it was primarily Sweden’s own citizens – not to mention the majority of the government – who were taken in by Erlander and Palme. By employing this rhetoric, however, they succeeded in isolating the Swedish communists to a marginal political phenomenon throughout the duration of the Cold War. This was the choice that both Erlander and Palme made. They likely realized that Sweden would not be able to avoid another great power war. Military geography worked against it. But by deferring the decision to join NATO, the prime ministers could maintain their majority for a long time. But would this tactic have worked in practice if the worst had come to pass? For Erlander, Norwegian NATO membership meant that the Nordic countries would be dragged into a third world war from the outset. As Erlander wrote in his diary: “The responsibility that Lange and Hauge are taking on should feel terrible, but it does not seem to bother them.”[40]

Until the 1980s, when mothers began to complain about their sons coming home in body bags from Afghanistan, Soviet leaders were not faced with any strong domestic protests against their foreign policy. The West did, of course, complain a bit when the Soviets had behaved extremely badly, but reverted to ‘business as usual’ after a few months.

A strong indication – though not necessarily proof – of Soviet Union culpability in violating Swedish waters is the similarity with other Soviet intelligence activities in Sweden, particularly the Professor class training ships. They served the same purpose as some of the submarines that visited Swedish waters, for example monitoring equipment trials and changes to the infrastructure along the Swedish coast, particularly to defense installations. The resources used depended on what they were looking for and what was best suited. Few have denied the existence of civilian midget submarines, painted in red and white stripes, in the Soviet Union. These were under the control of the Institute of Oceanology of the Academy of Sciences as were the training vessels, which means they were not truly civilian, like so much else in the Soviet state. The Russian Piranja class was also painted red and white for a time after the Soviet withdrawal from Latvia. Two of these had already been photographed in their dark military colors inside the submarine tunnel in Liepaja. In any case, the Piranja was reclassified as a military submarine again when they later tried to earn money from selling it.

In 1984, an article Jane’s International Defence Review (no. 11) shows a photograph of a Soviet midget submarine with a caterpillar tread, which was originally published in 1973 in Pravda. The photograph was taken west of Gibraltar, where it was said the submarine was searching for the lost city of Atlantis. It could not possibly have been searching for NATO’s military installations or lost equipment, could it? The article also states that according to a Soviet radio program of 10 September 1984, the submarine was still stationed there. So perhaps she, along with her support vessel, was the equivalent of the Baltic inlets’ ‘Watch Dog’, the colloquial term for Warsaw Pact vessels that monitored the Baltic.[41] The channels are considerably deeper in this region, so perhaps one surface vessel was not enough. This midget submarine can operate down to a water depth of 105 meters, unusually shallow for a research submarine. Of these there is a manned class, the Argus, and an unmanned class, called Zvuk (Russian for sound). Examples are also mentioned of mother ships for midget submarines, namely the Polish-built Vityaz and ‘the unknown’ Rift. These were also under the Institute of Oceanology of the Academy of Sciences, like the Akademik Aleksey Krylov, which appears in a photograph in the article by Jussi Lähteinen cited below. The latter has a hatch on the side of the hull, which seems suitable for one of the Spetsnaz units’ midget craft, the Triton 2.

In the Soviet Northern Fleet, there was an India-class submarine (NATO designation) with two smaller so-called rescue submarines in holes in the stern. These were, no doubt, also rescue submarines and, unlike the Argus, were deep draught; but at least one of the types was seemingly designed to be equipped with a caterpillar tread. A midget submarine with a caterpillar tread may be particularly useful when it comes to laying, maintaining, or picking up magnetic or hydrophone cables, an activity that was of relevance for their own harbor defenses, but also for investigating and destroying, prior to war, the SOSUS (sound surveillance system) lines that NATO had laid during the Cold War to keep tabs on Soviet nuclear submarines. The Soviet Union developed midget submarines with caterpillar treads for both civilian and military purposes. This is evident in two Russian books on marine research.[42] The earlier book contains a picture of a mother submarine with two machines with caterpillar treads connected; it is not evident from the picture whether this is for the power supply or steering, or perhaps both. In the photograph, a Russian-designed underwater machine, equipped with a caterpillar tread and a funnel to protect the cable attachment from the mother submarine or some other support vessel, is shown (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The former GRU colonel V. A. Plavins, who visited me in February 2007, was accompanied by a security man. He told me about a Soviet factory outside Liepaja which made underwater vessels with caterpillar treads like the one in the picture (Private archives).

One disadvantage with underwater craft equipped with caterpillar treads is the energy required for crawling on the seabed. There is, however, an example from the US that demonstrates that it is entirely possible to construct a self-sufficient version of such a machine. In the 1940s, the inventor Halley Hamlin designed a submarine that could travel a distance of 35 km at a speed of 4.5 knots and that was able to run for 32 hours on its batteries with a two-man crew.[43] At both Mälsten and Kappelshamnsviken, there were other indications that a mother submarine may have been involved and even been responsible for the power supply. The second photograph shows an older, well-used Soviet underwater machine, with something that looks like two adjustable engines so that it is able to lift itself up and float, for example up on a mother submarine (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. An older Russian-designed underwater machine (Private archives).

In the Swedish debate, some make the argument that even after the Cold War no one has been able to prove that the Soviet Union ever had the resources to undertake the incursions of which it was accused. Others, including Ingvar Carlsson, ask why, after the fact, those who were allegedly involved do not take responsibility. Both questions demonstrate a lack of thorough research. It is generally well known in military circles that at least from the beginning of the 1970s on, each of the Soviet fleets had a so-called Spetsnaz brigade with diving units for intelligence missions and marine sabotage. These also had the means to transport themselves further and quicker than by simply swimming from submarine torpedo tubes or from fishing trawlers outside the boundaries of territorial waters. Guide to the Soviet Navy, first published in 1970, states, for example:

Since the war, the Soviets have built several types of midget submarine, probably for offensive use in coastal waters. The first sighting of these types was during fleet maneuvres in April 1957. The incentive to build such craft was, no doubt, provided by the operations of German, British, Japanese, and Italian midget submarines during the Second World War. Three types are believed to be in existence, one being carried by a “mother” submarine . . . while the other two types are transported to their operational area by surface vessels.[44]

What follows is a specification table of these three types, called two-, three-, and four-man types, with lengths of approximately 13, 20, and 23 meters, respectively. Judging by the widths and heights, these vessels must have been rather clumsy in comparison with later models. These submarines, at least the three-man type, had the capacity to carry torpedoes. The book, which was written by Siegfried Breyer, a West German naval specialist who focused particularly on the Soviet Navy, has been continually reissued in new updated editions by the US Naval Institute in Annapolis. (It is worth mentioning that the 1970 edition states that the Baltic Fleet was still the Soviet Union’s largest fleet.)

I am not certain that these midget submarines were at the immediate disposal of the fleet units, but in any case, they later had other means of transport, such as the two-man wet Sirena and Triton 1, as well as one-man towing vessels, commonly known as underwater scooters. This did not prevent these midget submarines from being available for their disposal if necessary, much like the Whiskey class submarines.[45] The Sirena looks like a torpedo with special ‘saddles’ for its two ‘riders’. It can carry a nose charge, which can be used for various purposes when carrying out sabotage. Like the frogmen, she can pass through the torpedo tubes of a Whiskey class submarine. The Triton was further developed during the 1970s into a larger midget submarine with a length of 9.5 meters for two crewmen and four accompanying frogmen. The Triton is said to exist in both wet and dry designs and in a total of 24 types, i.e. about six per fleet. They were also the only underwater craft in the Baltic Fleet’s Spetsnaz brigade, according to Admiral Baltuska, who I interviewed in 2006 prior to an earlier project.[46] “I have personally been responsible for maintaining them,” he told me.

On 24 April 1998, Sweden’s FLT news agency issued a statement that also confirmed the existence of resources necessary for the Soviet Union having violated other countries’ waters:

Admiral Vladimir Kuroyedov says that this involves a special unit that exists in all four Russian fleets, in the Baltic, Northern, Pacific, and Black Sea Fleets . . . The fact that the Russian armed forces were equipped with midget submarines is nothing new. The Submarine Commission had already established this in its final report in 1995. On the other hand, the existence of special units has never been able to be confirmed before. . . .The Military Intelligence Service, the GRU [Soviet General Staff], organizes underwater forces that carry out secret activities against foreign naval bases. The GRU uses midget submarines that are the same length as those hunted by the Swedish Navy in Swedish waters. [47]

The last sentence refers to the Soviet (later Russian) Piranja, which has been in the Baltic since its 1984 prototype, when it was discovered in Swedish waters. On 19 August 2004, there was fresh confirmation in the form of an interview in Svenska Dagbladet with the commander of the Baltic Fleet, the Russian admiral Vladimir Valuyev, who was visiting Sweden while the Swedish submarine force celebrated its centenary year. In the interview, Valuyev stated: “Yes, we are equipped with midget submarines.” Already at the time of Kuroyedov’s statement, Interfax provided supplementary information by stating that the naval Spetsnaz units were set up in 1969, and that just a year later the GRU began to organize underwater forces under the name of ‘Delfin’. Their mission was to engage in covert activity against foreign naval bases in order to carry out intelligence and diversionary tasks. Delfin is probably a special unit under the direct command of Moscow, which carries out missions outside the Baltic. Admiral Baltuska also had something to say about this: At Kronstadt, there were approximately three 60-meter-long submarines that were not under the command of the commander of the Baltic Fleet, and which he believed carried out missions in the Atlantic.

On 22 September 1996, in a segment of the Swedish TV program Reportrarna [The Reporters], interviews were conducted with three men who had served on Soviet submarines. They all spoke of being in foreign waters. Swedish and Scandinavian waters were mentioned in particular, as were the Sirena and Triton submarines. During these programs (a second part, two weeks later, focused on nuclear weapons) the men related that while in foreign waters they were often subjected to depth-charge attacks, resulting in colleagues suffering panic attacks and sometimes even having to be restrained and anaesthetized until they reached port and could receive professional help. Sometimes fatalities occurred, particularly among the divers on missions outside the vessels. On one occasion, they got stuck in an anti-submarine net but managed to cut themselves free. The 1995 Submarine Commission’s report mentions that in 1986 the Swedish Navy discovered damage like this to a net across one of the entrances to Hårsfjärden, an incident that while of course not necessarily connected to the one referred to in the interview, could be. When I rewatched these TV programs in preparation for my book, I remembered a section from Lennart Ljung’s diary, dated 28 December 1982, almost three months after the Hårsfjärden incident:

I received a phone call from an editor called Teander from Nerikes Allehanda, who I already know. He has, among other things, studied at the National Defence College. He had two pieces of information, one of which was a West German statement that the Swedish and Soviet Governments had agreed to release a submarine. I was, of course, able to emphatically deny this. The other piece of information was more interesting. Teander had received information that a Russian citizen had visited a Swede in the Örebro area over Christmas. The Russian had mentioned at the time that he had a distant relative who had served onboard the Soviet submarine fleet in the Baltic. He had now been reported missing since the exercises took place in the western Baltic. He also said that the Russian had stated that it was said that several Russian submariners had been injured during this activity. The dates could have corresponded with the events in Hårsfjärden. I have got the intelligence people to do some discrete enquiries.

Has any country, other than Sweden and Norway, deployed depth charges and mines to combat submarine incursions in times of peace? Jussi Lähteinen, a Finnish captain, decided to explore this very question by utilizing the resources available. In an article he published, “Ubåtars territorialkränkningar – erfarenheter i Sverige och Finland” [“Territorial Violations by Submarines – Swedish and Finnish Experiences”], he describes the three aforementioned Reportrarna interviewees[48] :

A Russian submarine officer, aged around 40 and now in the reserve, provided details of the Sirena and Triton craft that were used on missions like this. He told how agents were transported on them. The divers could, for example, leave the mother submarine on an underwater scooter a few kilometers outside a harbor that was to be explored, carry out their mission and then return, usually in the early morning hours. It was easiest to operate in the evenings, at weekends, and in the autumn. This was when surveillance was at its weakest. The reason for this activity was to train in realistic conditions and to detect changes to the harbors. The submarine officer telling his story had frequently been in Swedish and other Scandinavian countries’ territories illegally. It was easy for the submarines to hide among the rocks in the archipelago. According to Russian information, several divers had died during these operations. As regards the Whiskey class submarine that ran aground in 1981, the officer stated that another Soviet submarine had also been at the scene and tried all night to pull the stranded submarine free.

The second person interviewed was a naval doctor, with the grade of commodore, and he stated that he had served on submarines for five years. His home station was Paldiski in Estonia. The officer said that he had taken part in many missions in foreign countries’ waters. He said that depth charges were often deployed against his submarine, and that it once got stuck in an anti-submarine net. The orders to penetrate foreign waters came from the general staff in Moscow. In practice, the operation was led by a GRU intelligence officer. The doctor mentioned reconnaissance missions and exercises as the reasons for the incursions. Good performances were rewarded with promotion. Twenty years ago, he had been a lieutenant.

The third person interviewed was a naval officer in uniform; he had served in the navy for thirty years. He had been the captain of a submarine in the Baltic. Before he retired, he had operational staff duties in Kaliningrad. He talked of the use of midget submarines for sabotage and mining missions in the harbors. The Sirena class diving craft, which were transported in torpedo tubes, became standard equipment on their submarines from the 1950s onwards. The people interviewed had also provided a lot of additional detail to the presenter, which confirmed their accounts.

Why do not more people speak up? But of course as a military professional myself, I understand well that special units of this type, particularly those that have been subjected to the kind of stress described in the interviews, develop an extraordinary loyalty to each other and to the organization. In addition, the GRU developed a fear of its organization that was at least on a par with the fear of the KGB. It was even a crime to talk of its existence. Our informant from the ‘Watch Dog’ disappeared before we had a chance to complete the debriefing.

Let me finish with an example from the International Commission of Military History’s trip to the former Soviet Union in the summer of 1992. A photograph from this trip shows a man leaning against a midget submarine, now displayed as an exhibit (Fig. 4). It was taken inside the naval base in Balaklava, to which the party was admitted by the former GRU officer Dimitri Bulovanov. When measured ‘through furtive pacing’, the result is that it is 16 meters long. It is spool-shaped, does not have a conning tower, and is dark-colored. According to Bulovanov, the submarine was built in the early 1970s at the Sudomekh shipyard in Leningrad. It could, therefore, have been extremely active in the 1980s and, if so, also in the Baltic.

Fig. 4. A Soviet midget submarine.

The description corresponds well with a phenomenon I have encountered many times at presentations on the submarine issue during my tenure as supreme commander. This phenomenon, the so-called ‘Whaleback’ effect, would cause a wash near the surface and often attract the attention of holidaymakers, but also more professional reconnaissance units. There was even a Politburo decision to send the Delfin unit to Swedish waters in peacetime. This information is available in a book written by the UN Under-Secretary General for Disarmament Issues Arkady N. Shevchenko, who defected from the Soviet Union.

In important foreign policy matters the Kremlin leadership’s typical double-handed approach was expressed in the approval of a plan to send submarines to probe Swedish and Norwegian coastal areas soon after Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme visited Moscow in 1970 and received assurances that the Soviet Union intended to widen the friendly cooperation with his country. At a meeting in the spring of 1972, it was decided to sign the convention on the liquidation of biological weapons. But General Aleksei A. Gryzlov told me that Defense Minister Andrei Grechko had instructed the military not to abandon its program to produce weapons. It is not possible that the Politburo was unaware of this order.[49]

These four sentences that Shevchenko provides in his extensive memoirs are the only examples of this recurring characteristic of the Soviet state’s notorious unreliability and double-handedness. As a naturalized US citizen, it was important for him is to inform his predominantly American readership of the risk of being attacked by biological weapons despite the UN agreement. His mention of the submarine incursions also spoke to the American public, as the 1981 ‘Whiskey on the Rocks’ incident had recently taken place and dominated front page headlines. And due to information now available, we now know that time-wise his assertions correspond well with the setting up of the new Delfin unit.

On 26 April 1983, the same night that Sven Andersson had been singling out the Soviet Union as the guilty party for the 1982 violations, Georgi Arbatov, director of the Soviet Institute for the US and Canadian Studies, was due to speak to a private audience of fewer than a hundred people at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. He purportedly spoke about the special responsibility that rested with the superpowers, the US and Soviet Union, with their large stocks of nuclear weapons. According to several sources, he also called Sweden naive if it believed that the submarine incursions would cease. Later that year, this same Arbatov told Palme that the Soviet Defense Minister Dimitry Ustinov had announced that he had ordered that no more submarines be sent to Sweden. About two months later, Nikolai Ogarkov, Ustinov’s successor, said the same thing to Anders Thunborg. In his diary on 17 August, Ljung noted: “This can also be taken as an admission of the previous incursions.”

May I conclude this list of indications that it was the Soviet Union behind these incursions into Swedish waters by mentioning that on 29 June 1988, while the incursions were still going on, Aftonbladet featured an article in which it claimed that a Soviet government official, an expert on Scandinavia, had stated that Soviet submarines had been operating in Swedish waters over the recent years. This was during glasnost and he thought that the submarine incursions had come to an end with Gorbachev. It is my opinion that during the Cold War the territorial waters of all the Nordic countries were at times violated by Soviet submarines. Most likely there were several different organizations – with different motives – responsible for these incursions. In the following passage I describe the units possibly involved and their possible motivations for visiting Swedish waters.

The Baltic and Northern Fleets’ Spetsnaz units could, in all likelihood, have been responsible for the coastal intelligence activity required for any landings in the event of war in Europe. (the Northern Fleet’s units in northern Norway, specifically, and the Baltic Fleet in general) Aleksandr Rzhavin has described this in ‘Navy Spetsnaz’, a translation by MUST (the Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service) of a Russian book, which was edited by the son of a Latvian Spetsnaz soldier.[50] In any plan, the intention was to destroy Swedish coastal sensors, as the Soviets were aware that the results from these were also reported to NATO, such as those from FRA (National Defence Radio Establishment) installations.[51] At a PHP (Parallel History Project) conference in Bodø in August 2007, at which I presented the findings of my earlier research of the Soviet threat against Sweden, the Russian general, Vladimir Dvorkin, also participated. He stated that the Soviet Union had assigned ten divisions to overpower Scandinavia. While the main target was certainly Norway, it was unclear how much the plan intended for Sweden to be affected. The forces to be deployed suggest that only the most northerly area would be involved for a reason that will soon be discussed.

Fig. 5. The invasion picture is taken from an article entitled ‘Khrushchev’s Right Flank’ which was written by US Colonel Robert P. McQuail (source: Military Review, no. 1, 1964). The arrows in the North Sea have been added by this author.