The Soviet Threat to Sweden during the Cold War

Introduction

In the summer of 2005, a study called Danmark under den kolde krig [Denmark during the Cold War] was published in Denmark.[1] In Sweden, this publication caused the biggest stir by accepting Ola Tunander’s theory that it was American submarines that – with the consent of some of those in central positions – violated Swedish waters in the 1980s. The Danish military also had a number of other views on the study and, in the autumn of 2005, the Danish military historian and retired Brigadier General Michael Clemmesen gave a lecture at the Swedish National Defence College in which he, among other things, gave an account of the plan for the Polish so-called Coastal Front’s attack along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea with the aim of occupying Denmark within two weeks. At the end of this lecture, he said that only a small number of units in the Baltic military district were involved in this operation and asked himself what their mission could have been. There were a few of us who made a mental note of this question and, since then, I have – with the support of Professor Kent Zetterberg at the Swedish National Defence College – devoted myself to trying to ascertain whether it is possible today to get a more factual answer to the question of the Soviet threat to Sweden during the Cold War, i.e., during the period 1945–1989/91.

The conditions for doing this appeared to us to be significantly worse than they were for the Danish researchers. Why this is will be explained in greater detail in the next section. Neither they nor we have had access to the various Russian (the former Soviet Union’s) security authorities’ archives regarding the Cold War era. In those cases where they have actually ever been opened, documents for the period up to and including the Second World War have primarily been available. For this reason, I have had to refer to open sources and interviews with former Soviet armed forces officers or others with an insight into Soviet society. There were, however, many books written by Soviet defectors around 1990 and the task I had taken on voluntarily was easier than I thought.

Some basic information

The Swedish Governments’ aim with our so-called policy of neutrality and our strong military defence for a small state was for us to be able to keep out of any Great Power conflict in the event of one of these, again, affecting our immediate surroundings. At the end of this essay, I will return to this choice of alternative and how this has turned out, in retrospect, in comparison with the alternative, i.e., joining NATO like Denmark and Norway. As they say, it is easy to be wise after the event.

From the middle of the 1960s, it is difficult to imagine that either of the two superpowers would deliberately start a war that could lead to a dual between them involving the use of nuclear weapons. There was, however, the possibility of a misjudgement or escalation from a small, local war. From the beginning of the 1960s, the Soviet Union adopted a pre-emptive strategy that led to the risk of this. What were the innermost thoughts of the US? (For an answer, see "The Creation of SIOP-62" by William Burr, The National Security Archive.)

The policies pursued by the Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact during the Cold War are summarised in the Danish study as follows:

As the Soviet Union chose the offensive as a strategy in its war planning, this became a considerable potential threat to Denmark, Norway, the Federal Republic of Germany and other states that would come into direct contact with the eastern war machine. If, in its security policy, the Soviet Union had chosen a more defensive policy, such as that introduced by Gorbachev in 1987, in which they restricted themselves to defending their own areas in the event of a war, the Warsaw Pact would have been perceived as considerably less of a threat.[2]Sweden belonged to these ‘other states’, although it was separated from the Soviet Union by Finland and the Baltic Sea. I should perhaps also remind the reader that the intrastate border between the Communist GDR and West Germany ran west of Skåne.

Only someone wishing to ignore the aggressiveness of the intelligence operations conducted against our country and the subversive political activity, which was of the same type as in the European NATO countries, could have perceived the situation differently. ‘From an intelligence point of view’, said a former officer of the GRU, the Soviet military intelligence directorate, ‘Sweden was regarded as an enemy’. (See as an example from the 1980s Document 1, obtained from General Kronkaitis.) I am not asserting that the Soviet Union had the political intention of starting a war to conquer Western Europe at a suitable time, only that it pursued policies that could be perceived as threatening and, at times, risky.

In an earlier paper, I touched on the ideas we ourselves had regarding the so-called threat Sweden faced during the Cold War, and how this resulted in operational defence doctrines and defence preparations.[3] The Danish study got me interested in testing the accuracy of these ideas. General information can be gleaned from the study, such as the view over time of the use of nuclear weapons. There are, on the other hand, few significant details to clarify the actual military threat to Sweden and the other Nordic countries.

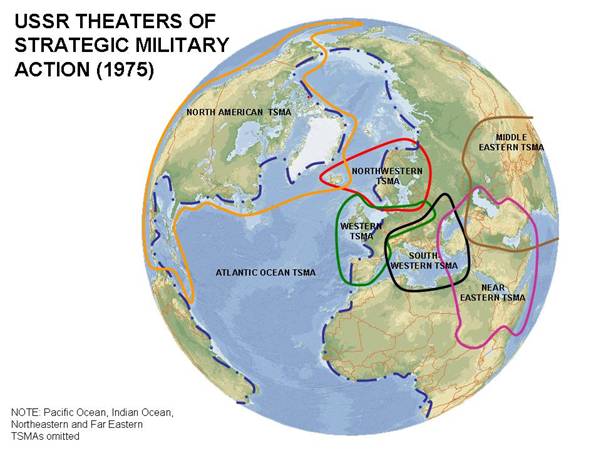

This is connected with the Warsaw Pact’s command structure and its ‘firewalls’ for operational planning. The latter appear to have continued all the way to the General Staff in Moscow who were (are?) divided into operational planning cells for the various strategic areas that the military geographical world is, according to the Russian model, divided into, the so-called Teatr Voenny Destvij [Theatre of Strategic Military Actions – TSMA]. Groups such as this left the Centre to conduct exercises with the regional staffs within the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact. Only very senior officials, and few non-Russian officials, had any knowledge of the operation order for higher units. The operation orders were handwritten and only a few copies existed. No one knew what applied within neighbouring TSMAs. So that this could work in the event of war breaking out quickly, sealed envelopes containing orders were held by commanders throughout the entire command hierarchy. This, of course, entailed a major risk of poor coordination during implementation. On the other hand, the concentration of force was a principal axis for each operational area overall.

Denmark belonged to the continental Western TSMA, while the other Nordic countries belonged to the Northwestern TSMA. There are some signs that the border between these TSMAs may have been somewhat fluid in order to allow operational flexibility, or may have changed over time. In the latter case, the southernmost part of Sweden may, at the beginning, or in the event of some war contingencies, have belonged to the Western TSMA. In this case, this would apply at the time of or in the event of Skånelanden becoming a part of the operation against the Baltic straits.[4]

Thus, the Danish study’s archival sources and witnesses from the Central European countries have few or no details of operational planning in respect of the Nordic countries in general. The available sources regard Skåne (a Polish exercise in 1954) and Southern Norway, which, from the end of the 1970s, was indicated to be a secondary target for the Polish Coastal Front after the occupation of Denmark. Therefore, we cannot obtain any details from the documents that remain in the Polish and the former East German or Czechoslovak archives or from the witnesses from there who took part in the meetings and exercises in the same manner in which the Danish researchers acquired about the plans for their country, which belonged to the same TSMA as these countries.

When mobilising, each Soviet military district would set up a front. The border within the Northwestern TSMA between these two military districts (fronts), Leningrad and the Baltic, was at latitude of about 60°. It is unclear where the land border was in the actual Soviet Union between the Western TSMA and the Northwestern TSMA in the Baltic. In The Voroshilov Lectures, there are two illustrations with different boundaries defined.[5] In one illustration, the boundary is in the Gulf of Finland, i.e., close to the latitude of 60° and, in the other, between Latvia and Lithuania. Was this just a mistake or was this changed over time, or did this depend on which of the TSMA’s operations the initially deployed units were involved in in each separate situation? It is also one thing drawing boundaries for peacetime planning and another in the emergency situation when war breaks out when the allocation of units and boundaries must be adapted to the actual situation. We can, however, establish that the immediately battle-ready two divisions in Kaliningrad Oblast travelled, on one occasion, in convoy on the Polish front on a map and, in other cases, they had the task of landing in the southernmost part of Sweden.[6] The latter may have been the case prior to the 1960 plan.

Upon the reunification of Germany, the high level of combat preparedness (hours) of units in Central Europe and the abundant use of tactical and operational nuclear weapons during staff exercises for the Western TSMA were revealed. Researchers have asked themselves whether these exercises were an expression of the actual operational planning. Through, among other things, the Danish study and testimonies in the international Parallel History Project (PHP)[7] it must be considered proven that this was the case. For a member of the armed forces, it is also natural to test the feasibility of one’s plans when carrying out exercises, particularly in those cases where the units involved in these exercises also participate in them. There were rivers that could represent the Rhine and islands that could represent those of Denmark. After Action Reviews were held after the exercises and sometimes led to changes to the plans. I have a copy of a handwritten plan from the PHP for the utilisation of the Czechoslovak People’s Army in the event of war (1964 edition) signed by the Supreme Commander of the Soviet armed forces, which tallies with the information about exercises from witnesses.

The pre-emptive Soviet strategy

During the so-called period of détente from the end of the 1960s, the Soviet Union intensified its rearmament particularly with regard to the Northern Fleet, which replaced the Baltic Fleet as the Soviet Union’s most prioritised Navy. The Central European Warsaw Pact countries’ armed forces were also modernised in order to be able to deal with their offensive missions within the framework of a new strategy.

This strategy meant that, when they deemed there were signs of an imminent NATO attack, the Warsaw Pact (admittedly, the Soviet Union) would pre-empt this so as to, as quickly as possible, render NATO’s deployment of nuclear weapons and American reinforcement from across the Atlantic difficult. The operational plan meant that the Western TSMA would be able to attack westwards from Czechoslovakia to Poland on a wide front and be able to reach the Atlantic coast in a few days. At the same time, they would attack from Hungary through neutral Austria towards northern Italy and the Mediterranean. A common thread runs through a meeting of the inner circles of the Soviet military at the beginning of the 1950s to Marshal Zhukov’s secret Berlin speech in 1957 to the decision in 1960 to adopt a pre-emptive offensive strategy. The meeting I mention was held just before the fall of Beria in 1953 and described in the memoirs of Stalin’s spymaster Pavel Sudoplatov:

Beria ordered me to, together with the chief of the GRU, General Zacharov, the chief of the navy’s intelligence operations, Vorontsov, and the commander of the long-range bombers, Marshal Golovanov, to come up with suggestions within a week as to how the American strategic air superiority and the American nuclear bases could be neutralised. He wanted a plan for putting the Americans’ lines of supply to Europe out of action, including ports and air bases.The following week, when we gathered in Beria’s spacious office in the Kremlin, the Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union, Admiral N Kuznetsov, was present… with a different perspective on the meeting. He said that emergency operations should be classified in accordance with the characteristics of modern war, and, he asserted, modern conflicts tend to be short and achieve ultimate decisions. On the basis of my plan, he asked the question: Given that we have limited resources, where should our priorities lie – in a pre-emptive attack that would, perhaps, sink three or four aircraft carriers at the Atlantic ports or in the Mediterranean or in blowing up naval bases to prevent the flow of troops? Based on his naval perspective, he asserted that, in the long term, we could, by depriving the Americans and British of their superiority with regard to aircraft carriers, shift the balance of power to our advantage and thereby increase the overall effectiveness of our submarine force. General Zacharov, who later became Chief of the General Staff, remarked that the idea of pre-emptive strikes against the enemy’s strategic installations was an original idea in the art of warfare and one which he suggested that we should seriously further develop (my emphasis).[8]

In March 1957, Marshal Zhukov gave a secret speech in Berlin to the officers of the Russian group in East Germany.[9] He probably wanted to strengthen the fighting spirit of this forward deployed group now that West Germany was going to rearm and nuclear weapons were deployed in the European NATO countries. (Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko and Defence Minister Georgy Zhukov were there to sign a defence agreement with East Germany.) In his speech, he emphasised that it was the Soviet Union that would strike first. As soon as there were signs of NATO preparing a strike in Europe, the Soviet Union would pre-empt this with a quick offensive right to the Atlantic. It was the well-equipped second echelon from the Belarusian and Baltic military districts that would be responsible for this. In the operation to counter the Hungarian Uprising the previous year, the force proved that it could be deployed in 46 hours. It was therefore this period of time that this forward deployed group would have to be able to hold its ground if – despite everything – the Western powers were to suddenly strike.

In reply to a question on why they could not get the same good armament, the Marshal said that it was important to let sleeping dogs lie. They were under constant observation from the other side of the border. He also discussed the fact that some of them had been too open with their East German colleagues. They just couldn’t be trusted. Some of them had defected to the West. It was vital to keep plans a secret from them. Although he spoke about the new nuclear weapons as the weapon that would destroy the opponent’s armed forces, he also said that they perhaps did not need to be used in the attack right to the Atlantic.

It was perhaps not such a great surprise that Zhukov of all people conveyed a perception such as this. He was, of course, a product of the ground forces, which had, historically, been the priority element of the continental power’s armed forces. Not everyone was delighted that the army was to be reduced, the navy to be expanded and the independent Strategic Missile Troops were to be prioritised. In addition, the Defence Minister had ideas about organising special sabotage forces within the framework of the GRU, which would have the primary task of making it more difficult for NATO to use nuclear weapons, ideas that he had ‘forgotten’ to brief his political colleagues on.

Already during the war, Zhukov had been seen as a potential rival for supreme power. (His home telephone would be tapped right up to his death.) Despite this, Khrushchev restored him to favour and appointed him Defence Minister. He had, of course, supported Khrushchev’s two-year long power struggle within the collective leadership after Stalin’s death. When, however, Khrushchev was made aware of Zhukov’s decision to organise these GRU forces (Spetsnaz), he got cold feet and regarded them as a possible instrument for a military coup and takeover. Zhukov was once again sent into domestic exile.[10]The new military doctrine was presented at the meeting of the Supreme Soviet on 14 January 1960 with heavy emphasis on the use of nuclear weapons.[11] The Soviet Union had quickly made up ground on the American lead and during the early 1950s they began to make operational nuclear weapons. The strategy was communicated to the Warsaw Pact’s defence ministers at a meeting at the beginning of 1961 and Marshal Sokolovsky’s detailed operational plan was submitted in the summer of 1962. I will return to this view of nuclear weapons further on in the section The European Nuclear War, which provides an overall discussion of this problem.

I will also provide an overall account of the Spetsnaz organisation later. Because, even though Zhukov disappeared, his organisation did not. It would be developed into a brigade at each front (military district) and fleet along with various units controlled from the ‘Centre’ for very secret and advanced missions. In connection with this account, I will also add to the submarine question[12] in those respects where the new facts have emerged from the sources I have now studied.

The Soviet strategic view of the Nordic region

Continental Europe or what the Soviet Union called the Western TSMA was therefore the strategic area that was at the centre of all thinking regarding how a military confrontation between the superpowers could be prevented, break out or accomplished. Great importance was, however, also attached to the Nordic region, i.e., the Northwestern TSMA, due to its flank position in relation to the Continent and NATO’s sea communications across the Atlantic. For the Soviet Union, Scandinavia was also an area over which air and, later, missile strikes could be directed not just at the satellite states and communications with them, but also directly at the Soviet Union’s heartland. The direction was what could be called the Soviet Union’s ‘soft underbelly’, an important area in its neighbourhood that it had no control over.[13]

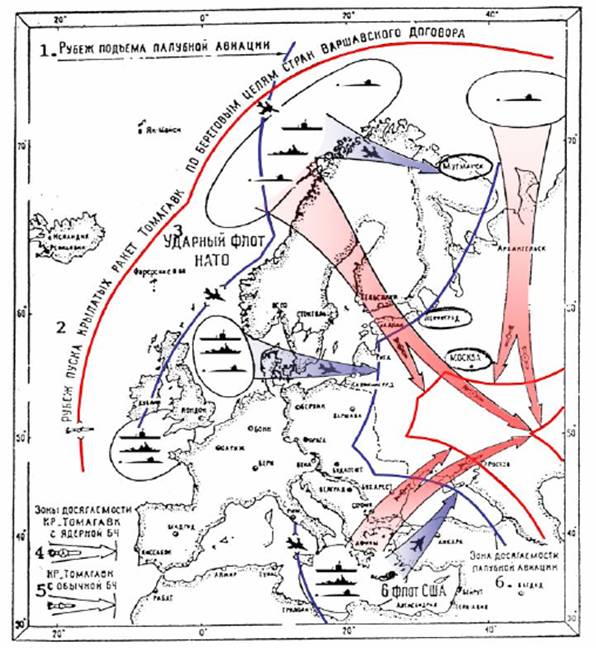

Illustration 1. The Soviet view of the 1980s with regard to threats coming from across Scandinavia. (Illustration from Lars Ulving’s Rysk krigskonst [Russian Art of War], Figure 2.27.) In the 1950s, the threat consisted entirely of strategic nuclear bombers with a need for support from tactical aircraft based in the Nordic region.

Illustration 1. The Soviet view of the 1980s with regard to threats coming from across Scandinavia. (Illustration from Lars Ulving’s Rysk krigskonst [Russian Art of War], Figure 2.27.) In the 1950s, the threat consisted entirely of strategic nuclear bombers with a need for support from tactical aircraft based in the Nordic region.

In The Voroshilov Lectures, there is a description of how, in the mid-1970s, the Soviet General Staff Academy regarded the Nordic area from military strategic points of reference. It says, among other things, that the Northwestern TSMA consists of Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland and the Northwestern Soviet Union and surrounding waters. It is explicitly stated that Finland and Sweden are neutral. As regards the Western TSMA, it is also said that ‘the Danish sounds are of vital operational importance. Here, close cooperation is required between ground and air forces and the Western Fleet’ (=The Baltic Fleet). The description of the Northwestern TSMA’s strategic characteristics continued:

The Northwestern TSMA at its western boundary meets the Atlantic Ocean TSMA, where large groupings of NATO naval forces are deployed. Important air and sea routes across the Atlantic Ocean connect America with Western Europe. Operations conducted in the Atlantic Ocean, particularly in its northeastern parts, will have close connection with operations carried out in the Northwestern TSMA, and will have great impact on the general strategic situation on the European continent.

In the south, the Northwestern TSMA borders the Western TSMA, where the most active NATO countries, primarily West Germany and England, are located. Strong NATO armed force groupings are deployed here, which is at the same time the centre of the main economic regions of West European countries. Lines of communication of worldwide significance pass through this area. Operations in the Northwestern TSMA will have to be coordinated with operations in the Western TSMA in terms of unified concepts and strategic political aims.

Illustration 2. The Soviet Theatres of Strategic Military Planning in the 1970s.

As discussed above, the Northwestern TSMA occupies an important strategic position between the West European TSMA and the oceanic TSMA of the Atlantic Ocean. In the context of NATO plans, the countries outside the USSR in the TSMA will be used as NATO´s bridgeheads for military operations directed to the east. That is the area where NATO has already deployed forces which will be employed to protect its northern flank to the Western and Atlantic Ocean TSMAs.

The main naval forces of the Warsaw Pact countries are deployed in the Northwestern TSMA. This area will provide favorable conditions for Warsaw Pact naval forces to get access to the northern and central Atlantic Ocean, which is under NATO control and influence. This action will isolate Norway and Denmark and provide suitable opportunities for the Northern and Baltic Fleet of the Soviet Navy, as well as for Poland and the German Democratic Republic, to accomplish missions for the purpose of destroying the main groupings of NATO forces operating in the Western TSMA.[14]

With a strategic view like this of the Nordic area, we undeniably get the impression that the Nordic area would be affected by any Soviet operation – and at an early stage – in any war on the European Continent. The question is how a militarily non-aligned Sweden would be dealt with in an operation like this in the Northwestern TSMA. A Sweden that would undeniably become isolated, along with Norway and Denmark.

Various plans

The Soviet view of an undesirable hot war with the other superpower varied over time and also depended, among other things, on the balance of power and the view of nuclear weapons. Initially, Stalin did not perceive the threat from the American nuclear weapons as particularly overwhelming. The people had just recently demonstrated what hardships they could cope with. Throughout history, Russian governments have demonstrated ruthlessness, particularly with regard to how they treat their own people. An old idea is that their losses would be even greater if they were not prepared to accept the initial losses in what would perhaps be the decisive initial battle. The old planning for the Nordic region from the 1940s probably lived on until the offensive strategy was adopted at the beginning of the 1960s. It was based on the perceived aerial threat around 1950, as the illustration above (see Illustration 1) shows and may have lived on as an alternative plan even later. In Wardak’s notes from the middle of the 1970s on the Soviet Union’s strategic view, the view of Scandinavia as a bridgehead for a strike eastwards lives on, as we see in the quote above, like in the Polish exercise in 1954. I will return to this below under the heading The Invasion.

When, from the middle of the 1950s, the Soviet Union envisaged its own substantial possession of nuclear weapons, including hydrogen bombs, Khrushchev relied on this new weapons system, which was prioritised and became an independent branch of the armed forces at a strategic level. We had a period when both sides could envisage that any war between them would be a nuclear war with ‘mutual destruction’, which they also hoped would mean ‘mutual restraint’ from war as a whole and particularly in Europe. In order to ensure this restraining capacity, Khrushchev tried to supplement his first intercontinental ballistic missiles’ lack of precision with the forward deployment of intermediate range ballistic missiles in Cuba. His adventurousness thus created – a short time after the ‘Second Berlin Crisis’ – a new serious crisis in superpower relations, which would make both parties reconsider their nuclear weapons strategies.

In 1957, Admiral Sergei G. Gorshkov was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Union’s four fleets and convinced Khrushchev that they could not be a superpower without declaring their oceanic interests, which resulted in the fleets being heavily rearmed, now with a concentration of force in the Northern Fleet and also, from then on, in submarines, which were eventually to become nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed.[15] Admiral Baltuska recounts that he had to learn English as early as during naval officer college around 1960.[16] The reason was that officers would be able to work as ambassadors for the socialist system during peacetime naval visits. Gorshkov’s ideas in Seapower of the State also characterised the above description of the Northwestern TSMA in the last sentence quoted, in which Gorshkov’s speech can be understood that the Navy is also an excellent instrument for engaging ground targets.

Khrushchev was deposed in October 1964, with, among other things, the support of – some people say on the initiative of – the military-industrial complex. The reduction in conventional ground forces which was started was stopped and qualitative rearmament of offensive manoeuvre groups began. Airborne troops and the naval infantry were developed. The balance of power in Europe from the 1960s shifted more and more to the advantage of the Warsaw Pact, while the US was casting its gaze over South-East Asia.

Once the US had ended – and had, as a nation, recovered from – its involvement in Vietnam, it showed a fresh interest in the situation in Europe. At the end of the 1970s, the US began a new period of rearmament and encouraged its NATO allies to modernise their defences. NATO countries, it was claimed, should increase their defence budgets every year by 3% so as to be able to keep up with technological developments, while retaining their number of forces so as to be able to counter the rearming Warsaw Pact. With its new naval strategy, the US also became more visible on the Northern Flank of Europe. West Germany responded by developing its Navy, which, in the 1980s, began to operate further north in both the North Sea and the Baltic Sea and along with supporting Tornado aircraft.

With the development of electronics, the Western powers began to acquire what came to be called smart weapons; also a technological leap for the conventional armed forces. This was noticed during Israel’s attack on Lebanon in 1982 when the Soviet-armed Syrian air defences were quickly destroyed. Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, still the Chief of the General Staff, went on a visit to study what had happened. At the same time, Yuri Andropov, Head of the KGB since 1957, became the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and his tendency to overreact, which had become well-known from his ambassadorship during the Hungarian Uprising, was to lead to a new period that was full of risks.[17] The 1980s are discussed later in a separate section called The Period of Uncertainty.

In the following, I will report on the result of my studies of the Soviet military threat to Sweden during the Cold War as it appears from the available sources. I will begin with the most likely attack scenario in the Northwestern TSMA during most of the Cold War (Encirclement), as this alternative is the one that emerges most clearly from my sources. What I am talking about are intentions. That is not to say that these plans were also feasible. This question will be discussed in connection with every alternative individually.

Encirclement

The operational plan for the Polish attack along the southern Baltic coast is described in great detail in the Danish study’s report. It is also reported in an article in the Polish newsmagazine Wprost on 23 June 2002 by Pawel Piotrowski.[18]This plan had its early origins from before the creation of the Warsaw Pact. Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, one of Stalin’s most useful commanders during the Great Patriotic War, appointed to the role of Polish Defence Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, carried out exercises in this, probably with the consent of Stalin, as early as the beginning of the 1950s. Like other Warsaw Pact exercises, it was ‘the imperialist NATO’ that started the war, but not just from Denmark but, in this case, also from Sweden. In the Polish counterattack, the neutral country would therefore be invaded across the south coast of Skåne. The Danish study has not found any further evidence of Swedish involvement except for this exercise from 1954. On the contrary, they say that the Soviet Union later expected Sweden to remain neutral in the event of an attack on Denmark. The Swedish historian Carl-Axel Gemzell even says that he found out from East German sources that the Swedish declaration of neutrality was a secondary reason for the early occupation of Denmark.[19]

Illustration 3. Map from a Polish exercise in 1954, taken from Denmark during the Cold War. The map illustrates an amphibious operation against the Danish islands Sjaelland (upper left corner) and Bornholm (right), southern Sweden (top).

When the Warsaw Pact was formed in 1955, Poland wanted to continue to directly command its armed forces independently and was allowed, within the Pact, to retain this mission against Denmark within the framework of the offensive strategy. In the operational plan, which was established in 1961, it was the Polish armed forces that were to form the vanguard. The forces Zhukov singled out in Berlin are, however, part of the second echelon, which was to follow close on the heels of the Polish units. Although they trusted the Communist elite they put in power, the Russians did not have great confidence in the repressed people, which Zhukov remarked upon in his speech, that the Poles were regarded as requiring a controlling power. Later, the Soviet Union was to rely more on the East Germans than the Poles. For a while in the 1980s, the GDR even took over in planning the Polish mission against Denmark.[20] When I accompanied the General Director of the Civil Defence on a visit to Poland at the beginning of the 1970s, the usual joke among the elite we met was also about Russians who had made fools of themselves. Jaruzelski restored what was to prove to be a treacherous system. The Solidarity Crisis was actually to be the beginning of the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the end of the Cold War.

According to Piotrowski, in the plan (OP 61) the Polish First and Second Armies would attack Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein. In two or three days, they would break up the Jutland army corps and reach the Elbe and the Danish-German border. In the second phase of the operation, they would reach the Rhine and Moselle over the plains of Lower Saxony and Holland. It was the Polish Fourth Army from the Warsaw area that, somewhat reinforced, would succeed in the actual attack on Denmark. It was more poorly equipped than the forward-deployed armies and its most important reinforcement at the beginning of the 1960s was the deployment of nuclear charges against air bases and population targets, including Hamburg and Copenhagen.

The attack on Jutland would be facilitated through Russian airborne troops taking the Kiel Canal at an early stage. East German units would take part in landing on the islands. The Soviet Baltic Fleet would open up the Danish sounds and the East German Navy the Kiel Canal. The landing areas on the Danish islands were to be attacked first using highly volatile chemical weapons. In the event of nuclear war, the Poles themselves anticipated losses of up to 50% in the units deployed during the first few days.[21]

In Russian thinking, the replacement of personnel is by means of the deployment of new units and not through providing individuals to cover the units’ losses. This principle had already been applied prior to the advent of nuclear weapons and its purpose was to maintain the speed of attack. They were prepared for major losses.

In the Danish study the missions of the combined Baltic navies (from the beginning of the 1980s a combined Warsaw Pact Baltic Navy) are accounted for in connection with an attack on Denmark as follows:

- Destroy the enemy forces in or on the way into the Baltic Sea.

- Occupying the Danish sounds.

- Create the conditions for transferring naval forces to the North Sea through cleared routes.

- Create monitoring and base systems in the area.

- Transfer the combined Baltic Navy to the North Sea and Atlantic.

- Operations against the enemy’s lines of communication at sea and safeguarding their own lines of communication.[22]

These are very offensive ideas that we ourselves primarily associated from the 1960s with the increasingly stronger Northern Navy as regards attacks against the transatlantic routes. An example of how Swedish circles regarded the Baltic Navy can be taken from the 1984 Committee on Defence’s report Svensk säkerhetspolitik inför 1990-talet [Swedish Security Policy for the 1990s]: ‘… in the event of a protracted conflict, it may also be expedient to attempt to open up the Baltic straits in order to utilise the Baltic Navy’s base resources and naval armed forces’.

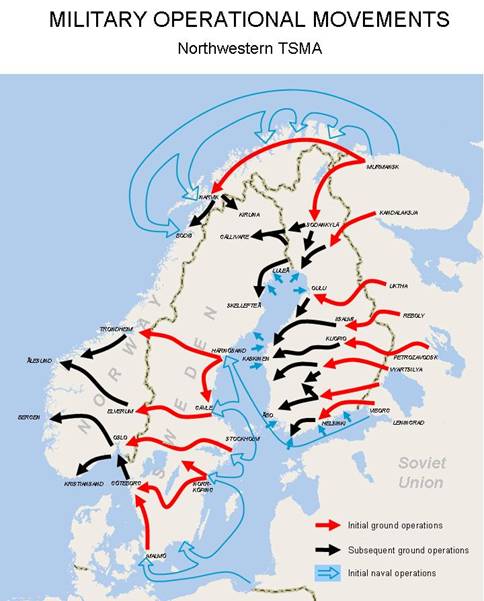

When I spoke to Admiral Zeibots[23] he said emphatically that, during his entire period of service from the beginning of the 1960s in the Baltic Fleet, he had been trained to break out through the Danish sounds – if necessary by means of nuclear weapons – and on to the gap between Greenland – Iceland – Great Britain, the so-called GIUK Gap, to engage Anglo-Saxon aircraft carriers and nuclear-armed vessels. (Baltuska, who was trained somewhat earlier, speaks of a second phase. I will return to this further on.) According to the plan, Denmark would be occupied in less than two weeks. The East German Navy would establish a naval base for the North Sea in the German Bight through the navigable Kiel Canal. From the second half of the 1970s, when the quality of the Central European Warsaw Pact’s armed forces had been improved, the Polish operation was to be extended to Southern Norway.[24] Did the Soviet second echelon have this mission previously?

In August 2007, a PHP meeting about the Northern Flank was held in Bodø. The retired Russian Major-General Vladimir Dvorkin, a specialist in strategic nuclear weapons strategy, and Professor Vitali Tsygichko were present. The latter, whose work during his active period appears to have been similar to that of our operational analysts at the Swedish Defence Research Institute, had also been present at the round table held in Stockholm in the spring of 2006 and was now also the Russian who spoke most. Among the things he said was that, prior to the meeting, he had studied plans from the 1970s and 1980s and found that ten Soviet divisions had been earmarked for the occupation of Southern Norway. Our understanding was that it was they who would follow after the Polish Coastal Front across Denmark. In reply to a direct question, Tsygichko said that he ‘did not see any war games that included Swedish territory’. He also said that the Soviet Union was of the opinion that ‘the probability to overcome the Swedish defence was low’ – a wording that indicated that the conditions of the time were not deemed to allow an attack on Norway across Sweden. Of Norway, he said that another option was taking important Norwegian coastal areas from the north by means of airborne and amphibious units, in roughly the same way as the Germans had done in 1940. (This was the same expression as I had used in my review the day before of a possible invasion of Sweden; see Illustration 7.)

Tsygichko also emphasised that both the Northern and Baltic Fleets’ operations were intimately linked to land operations, in which the opening up of the Danish sounds was the key mission. If the ground forces could quickly occupy Denmark, the Baltic Fleet could get out into the ‘blue waters’. The previously described missions for the Baltic Fleet out towards the GIUK Gap could reasonably be a joint one with the Northern Fleet, which should have had the prerequisites for getting there first. Zeibots does not, however, have any knowledge of how operational coordination such as this would occur. Baltuska is aware of a link. From 1976, when the old nuclear-armed Golf submarines were transferred from the Northern Fleet into the Baltic Sea and placed under the command of the Navy there, they were given, among other things, the task of supporting the Northern Fleet against the air base in Bodø. What else do the sources say about Arctic Scandinavia?

One early source in my investigations was a report (Document 2) on what Lieutenant General Vladimir Cheremnikh, First Deputy Chief of Staff for the Leningrad Military District from 1982–1986 (and earlier in the 1970s), said at a seminar in Oslo in 1994. He indicated, among other things, the primary targets for the military district’s front in the event of an attack on Arctic Scandinavia. The aforementioned Bodø was included in these targets, but also Boden. An interesting target itself, with Sweden’s biggest army garrison, but what was perhaps more important was that, via Boden, the Soviet Union could acquire a railway connection through to Narvik in Norway. (The Soviet Union was perhaps counting on using the railway network without fighting, like the Germans in 1940–1943.) No other targets in Sweden were mentioned. On the other hand, several targets were mentioned on the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, from whence troop transports could be made to the Norrland coast in Sweden. During an exercise in the middle of the 1970s, this was exactly what they did. In reply to the question of how far down the country this attack would reach, the answer was that it would, in any case, extend south of Stockholm.[25]

During this exercise the staff in Leningrad also anticipated that they would, as a result of the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, be able to gain access to roads and railways through Finland without fighting, a starting point that, in the light of my knowledge of the feelings of the Finnish people, appears unsound. The Soviet Union also attempted to guard against this uncertainty and ensure rapid success in Northern Norway. At the beginning of the 1970s, they therefore put forward a proposal for the Soviet Union to take over the defence preparations for the northern part of Finland within the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance.[26] A reinforcement of the defence of the Murmansk area, yes, but also an improved starting position for an attack on Northern Norway. However, this measure would surely also have provoked a change within NATO. Norway would, perhaps, have reviewed its base policy and requested that US troops were constantly deployed in Norway, even in peacetime.

Illustration 4. Taken from notes by the Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters/Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service. Report from Lieutenant General Vladimir Cheremnikh’s visit to the Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO), in June 1994.

The picture emerges that the pre-emptive offensive strategy also applied to the Northwestern TSMA and that the Soviet Union had, in this case, the objective of establishing what could be called a maritime defence zone west of the Nordic region, which would thereby be isolated in its entirety from the Anglo-Saxon world. Through the rapid occupation of Denmark and Northern Norway, they reckoned that Sweden would declare itself neutral and that Finland would adhere to what the Soviet Union interpreted as the spirit of the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance. The advantage in this for the Soviet Union was that there would be no need to detach forces to militarily defeat Finland and Sweden. In the case of Sweden, it could be perceived as particularly important at the beginning of a war not to be forced to neutralise the large air force and the Swedish Navy in connection with the break-out through the Baltic straits as this would require deploying forces that could be better used against NATO. In order to achieve success against NATO, it would be vital to reduce their naval and air forces from the outset, which had already been indicated at Sudoplatov’s meeting in 1953.

It proved to be the case that many had come to roughly the same conclusion long before, and one of those who described this was the Norwegian Rolf Tamnes, who has specialised in the study of developments on NATO’s Northern Flank during the Cold War. He quotes the Norwegian Ministry of Defence’s assessment in 1973 after a two-year in-depth strategic study of Russian intentions in the North:

The Ministry concluded that ‘the pattern of development appears to indicate that the Soviet defence zone is projected from the most northerly part of the Norwegian Sea to cover at the present time the whole Norwegian Sea in the waters of Britain, Ireland and Iceland’. The Parliament Defence Committee emphasised in February 1973 that the Soviet defence zone has now reached the GUIK line and ‘most of Norway is behind this line...’[27]

Illustration 5. The likely Soviet objective for the operation in the Northwestern TSMA during the period 1960–1987: to establish a maritime defence zone in the Norwegian Sea down to the North Sea. They were counting on Sweden remaining neutral in the event of a quick strike against Denmark and Northern Norway.

A frogman who belonged to the Baltic Fleet’s Spetsnaz unit in the middle of the 1970s (561st OMRP) confirms this conclusion when he writes in his memoirs that there were maps on the walls of the Spetsnaz training rooms that showed the locations for reconnaissance for landings. Along the operational axis in the northern Atlantic, the following targets were circled: Lofoten, Västerålen, the Faroe Islands, the Hebrides and Shetland Islands, the Bergen-Stavanger area in Southern Norway, the east and west coasts of Iceland and the southeastern coast of Greenland – a ring around the Norwegian Sea![28]Previously the Norwegian researcher Kirsten Amundsen had stated that ‘the Soviet Union needed Svalbard, Jan Mayen, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and the Shetland Islands’ air bases for fighter and bomber aircraft, electronic warfare, warnings sensors and harbours for submarines and other vessels’.[29] The Warsaw Pact also had offensive engineer units for repairs and the rapid extension of harbours and airfields.[30]

For example, Tsygichko’s mentioning of the ‘German-like’ option above can be regarded as an option of setting up a forward base area in the Bergen-Stavanger area. This would be as a compliment to another forward Soviet base in the Lofoten area and the previously mentioned East German base in the German Bight for support for the maritime defence zone in the expectation of Southern Norway being taken from Denmark. He also confirmed the Soviet interest in the islands in the Norwegian Sea.

In Military Objectives in Soviet Foreign Policy[31], Brookings researchers have, for their part, come to the conclusion that control would be taken of the Norwegian Sea in a later phase and that an invasion of Great Britain would be part of this phase. Admiral Baltuska also assigned the Baltic Fleet’s advance to the GIUK gap to a second phase, following the occupation of Denmark. This does not, per se, need to have meant that any let-up was planned between these events. What suggests that there would not be a let-up is the fact that the operation probably required the Soviet Union having to make the most of the element of surprise. It would probably also have been essential to be able to engage shipping across the Atlantic at an early stage, which was, of course, one of the aims of the pre-emptive strategy out towards the Norwegian Sea. Any attempt to invade Great Britain would, on the other hand, require practical preparations after the first phase, but it would certainly be easier to achieve if they had sufficient control of the Norwegian Sea’s sea room and airspace. The Golf submarines’ missiles in the Baltic Sea also had Great Britain as a target area. UK air bases should then have been an important target even before any attack on Denmark.

Was this then a realistic plan? A decisive factor was the element of surprise that the Soviet Union could achieve with the high state of preparedness of the first echelon’s units and the ability to easily utilise civilian resources, such as ships and transport planes. During the exercise I mentioned above involving the Leningrad front, the idea was initially not to use airborne troops in the surprise attack on Northern Norway and only troops across the sea mainly loaded onto civilian vessels. The relative strengths in the North in the 1960s and 1970s also indicated that this operation could meet with success; particularly, as they were counting on the deployment of Spetsnaz units and long-range aircraft reducing the Anglo-Saxon forces at an early stage.

What is more uncertain is whether the Soviet Union could have succeeded in creating the situation in the air that this very broad offensive would have required. It should, however, be stated that NATO’s air forces in Europe in the 1960s were not entirely modern and the Soviet aircraft with the armaments they had at the end of the Cold War proved to be superior to the Western side’s in a dual between individual planes (a German source after reunification). The development of electronics in the West and its importance for sensors, countermeasures and homing devices as well as systems integration created, however, a technological gap in the 1970s, which was perceived as troublesome in the East. According to Tsygichko, the Soviet Union’s evaluation following the war in Lebanon in 1982 resulted in the Warsaw Pact, during a war game, losing 80% of their vessels in the first two-three days and losing the battle for the Baltic Sea and the Danish sounds.

The offensive right to the GIUK gap would surely, even in the 1960s and 1970s, have required the greatest ruthlessness and speed the Soviet Union believed it was capable of. What is, of course, vital when choosing a plan is that those implementing it believe in their own ability and the Soviet Union’s leaders, including the General Staff, had, due to their strong ideological roots and the decisive military and political victories of the 1940s, long shared a great belief in their capability and their armed forces.

In the next section, I will discuss nuclear war in a context, but before that I have some comments on the operation described here within the framework of a nuclear war. The side striking first by means of nuclear weapons would, of course, have been able to inflict the greatest losses on its opponent, as well as on the latter’s nuclear potential, its naval and air forces and their command. Thus, a nuclear first strike would have favoured the Soviet Union and its possibility of taking over immediate control of the North Sea-Norwegian Sea area. Whether they could then retain this control over a period of time and how important this would then have been would have depended more on NATO’s second-strike capability and how this was deployed than who controlled the sea area at the start of an all out nuclear war.

The European Nuclear War

The advent of nuclear weapons would change politics and – if they were used – the war environment forever. As long as the US had a monopoly on them, they could still be used to continue politics by military means, according to Clausewitz’s thesis. It was a weapon that would be crucially decisive in war. The US could achieve its political objectives simply by threatening to use this ultimate force. But when there are two or more powers that have this new weapon, an entirely new situation arises; and this was soon to be the case.

Illustration 6. Aerial photo over the four missile silos at the nuclear weapons base in Ploksciai, Lithuania. From the underground command post tunnels led to the four silos. The entrance to the complex is visible in the centre of the photo. (Photo: Vidmantas Bezaras)

Was this threat then no longer practicable? Yes, if you struck first and were so numerically superior and could deploy your weapons so precisely that you could count on wiping out almost the whole of your opponent’s capability. If this were the case, would you even be able to resist doing just that? The opponent could, perhaps, do this in a later situation and then practically wipe out the very people whose well-being they, as a decision-maker, had responsibility for. It became necessary for each party in the nuclear world to ensure that they had a second-strike capability, a capability that would make the opponent unsure of whether you could, despite everything, strike back after a first strike. It was not until this balance existed that nuclear weapons were made unusable – there was a stalemate situation.

According to Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense during most of the 1960s, you would have a sufficient second-strike capability if you had so many and such diverse nuclear weapons that you could respond to the opponent’s first attack by wiping out up to 50% of his population and 65% of his industrial capacity. At the beginning of the 1960s, ‘Mutual Assured Destruction’ (MAD) acted as a major restraining factor at a strategic level between both superpowers. The US even exaggerated the Soviet capability. Another alternative would be if you had such a defence capability against both ballistic and cruise missiles that you could ward off a sufficient element of a first strike. At the beginning of the 1960s, the US began to develop such a system, which led to negotiations, and, in 1972, to the so-called ABM Treaty between the superpowers. This agreement restricted the number of systems that each party was allowed to have to a single one. The Soviet Union was the only country to develop such a system (around Moscow). The US instead responded by developing a system with multiple warheads on each missile, the so-called MIRV. When Reagan took over, however, he returned to the concept of defence with his ‘Strategic Defense Initiative’, a decision whose economic consequences for the Soviet Union would be a contributory factor to the end of the Cold War.

The argument must be made at two levels, both the strategic level, which concerns the superpowers’ own survival, and the theatre of war level, which concerns a local region in which the superpowers’ interests clash, e.g., Europe. Was a local war, restricted to this region, where tactical nuclear weapons – a kind of heavy artillery – were primarily used conceivable, and without resulting in an escalated exchange of blows at a strategic level between the superpowers? Was this conceivable? This would involve the superpower that was first to use nuclear weapons deliberately deploying them so that the other superpower had the option of responding in the same local region – and also doing so – and the exchange of blows remaining within this region. For example, NATO targeting its initial efforts, within the framework of ‘Flexible Response’, at the Polish river crossings and the Warsaw Pact responding by engaging, for example, the air bases in Western Europe. It is little wonder that anti-nuclear movements greatly increased in Europe.

The British nuclear weapons were incorporated into NATO’s planning and collective decision-making systems, so they did not cause either of the parties any particular problems. It was a different case with the French ones, which were national. The French president persisted in deciding himself when they would be used. According to the stated doctrine, this would not occur until French interests were threatened; therefore, at the very latest, once the French border had been crossed. In retrospect, it can be stated that, despite this, France was also included in the targets to be occupied in the Warsaw Pact’s initial offence right to the Atlantic. Targets, such as Lyon and Paris, are mentioned in the plan, the former as a target for the Czechoslovak People’s Army in the previously mentioned handwritten plan from 1964 established by the Supreme Commander of the USSR’s armed forces.[32]

At the tactical level, this initially concerned short-range tactical nuclear weapons. Both sides were well-equipped and maintained a high level of preparedness for deployment. NATO’s doctrine in Europe involved dealing with the dilemma of wiping out the opponent’s armed forces (which by definition were, in such a situation, advancing in Western Europe) without destroying its own infrastructure. NATO had, therefore, pre-selected a number of targets, against which they could deploy tactical nuclear charges against the Warsaw Pact’s strike forces and, at the same time, minimise damage to its own society. It was quite simply the case that this also made it impossible to maximise damage to the opponent. The US attempted, therefore, to introduce the neutron bomb, which would destroy people, even in armoured vehicles, through intensive radiation but which, thanks to a reduced blast, spared the infrastructure and materiel. At the end of the 1970s, further opposition to the European battlefield weapons arose, and I will return to this.

With the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, their earlier exercise scenarios, which we found out about upon German reunification, caused a great stir in the West, precisely because they often involved the use of nuclear weapons. It is not clear from these, however, how the Soviet Union perceived the global framework and how the overall trial of strength with the other superpower was intended to take shape in parallel with the European war. This question came up at a PHP meeting in Stockholm in the spring of 2006 – twice. It was an American general who asked the question about what the Soviet Union would have done if a European war had developed into a nuclear war. Would they then have deployed strategic weapons against the US? The reply from the Russian participants was yes – both times. Baltuska and Plavins share the same understanding.

The advent of nuclear weapons complicated not only politics, but also military activity in a completely different way to any other military technological development both before and after – in any case so far. In practice, ground warfare became almost impossible by the felling of forests and piles of rubble in urbanised areas, which, in the worst case scenario, would be contaminated by lingering radiation. The base areas for ships and aircraft, with their craft present, could be made unusable for a long period of time. More effective chemical and biological weapons could make the battlefield even more impossible to operate on. The professional corps acted as normal by developing methods and tools for overcoming these difficulties but the methods developed can only counter limited use and still at a high price. Man had, in principle, created the weapon that would, in the thinking of Alfred Nobel, make traditional warfare impossible.

A political objective could, of course, be achieved through a limited nuclear war, restricted in terms of both the power of the weapon – to tactical nuclear weapons – and the geographical spread, e.g., to Continental Europe. But how do you ensure that the intensity and spread do not escalate? And all-out nuclear warfare, even if it is of a short duration, can hardly be reconciled with any political objective.

Does all this then mean that we can rely on nuclear war being an impossibility? No, quite simply because the party striking first will have reduced the damage the opponent can inflict on this party and also, perhaps, considerably. Nor can we ignore human failings. We can, however, state that nuclear weapons were not used during the Cold War, despite this being characterised by great ideological antagonism that involved the majority of countries on the planet in some way or another. The balance of terror worked – and what is more, we did not see any conventional wars that openly involved both superpowers. The ‘Third World War’ of the 20th century never came to pass. Nuclear weapons must have contributed to this. Through their existence, the Cold War became so protracted that it made it possible for the indirect strategy of superiority in what came to be called soft power to prevail.

Changed conditions since the Cold War may have created new risks. The ongoing nuclear proliferation to more states increases the risk of the human factor taking its toll. Especially as technological developments are moving towards smaller charges with less of a destructive effect. The recent, more ruthless, fundamentalist terrorism can be considered to be a player that, if it acquires access to these weapons, could use them, fortunately only in small numbers. For Russian control during the break-up of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s was clearly not entirely watertight. General Aleksandr Lebed has pointed out that they did not know how many so-called ‘suitcase bombs’ were delivered to the Spetsnaz units (see below). According to reports, the German General Jörg Schönbom, who had the task of incorporating the East German Army into the West German one, discovered to his surprise 24 type SS-23 missiles on his visit to Brück on 8 January 1991.[33] Is it by any means certain that there are no nuclear weapons still adrift in the hands of international criminals? What suggests that this is not the case is the fact that none of these have been used in the recent, more ruthless terrorism we have experienced.

At the beginning of the nuclear age, Stalin was, as previously mentioned, not very afraid of America possessing nuclear weapons; not to the extent that he decided not to acquire these weapons himself, but he was not agitated enough to desist from deliberately manufacturing the first Berlin Crisis. It was not until the time of the Korean War that the Soviet Union began to organise its network of agents who would monitor whether American nuclear weapons were also being prepared for use. [34]

Stalin had known since the start of the war that the Western powers were carrying out nuclear weapons research. He was aware before Vice President Truman that the Manhattan Project was ready for testing. Both intelligence services, the political service (called the KGB from 1954) and the military service (the GRU), had been monitoring activity in the US, Canada and the UK during the war and had acquired useful technical knowledge. This was reported to their own research organisation little by little, which, after the end of the war, was bolstered with German scientists. Beria was given the administrative responsibility for speeding up the development process. The first atom bomb test was carried out as early as 1949, about four years after the US, and the first hydrogen bomb in 1953, only one year after. The first intercontinental ballistic missile, although it had poor accuracy, became operational in 1957, a year before the US – an impressive feat!

Khrushchev had a positive view of the role of nuclear weapons. Under both these ‘umbrellas’, he saw a certain political freedom of movement, but if there were to be a major war between the superpowers, this would be a nuclear war, which the Soviet Union could also win. The Soviet people could tolerate any hardship. The mechanised units would be sent into and through contaminated area as if they were invulnerable. What was important was simply striking first and critically decimating the opponent’s nuclear weapons. This would be ensured through the network of agents that had been organised to monitor preparations for any deployment of nuclear weapons on the part of NATO and their own political decision-making ability. They also organised secret special units (Spetsnaz) that had the main task of eliminating as much as possible of the opponent’s nuclear capability through sabotage or directing aircraft and missiles at warehouses, carriers and command systems right at the start of a war, whether this was a conventional war or a nuclear war. Plavins called these missions for ‘kamikaze soldiers’.

Soviet thinking at the end of the 1950s was to, as soon as war broke out, begin the massive deployment of both long- and short-range nuclear weapons, take the strategic initiative and decisively reduce both the opponent’s combat effect and his endurance. The targets for the missiles were NATO’s ports, aircraft carriers, air bases, troop concentrations and built-up areas of political, industrial and economic importance. On the actual theatre of war for the ground combat units, the front was the decisive actor. Based on the result of their own intelligence services, they themselves chose the targets to be engaged with the nuclear weapons put at their disposal. During exercises in Central Europe the fronts used up to 60% of these as early as during the first two or three days. In addition, there were those targets selected at the strategic level. In the Coastal Front’s operation against Schleswig-Holstein and Denmark, more than 200 nuclear charges were used during an exercise, some of which were against populated targets, such as Hamburg. As regards ground operations, the Warsaw Pact expected to attack at three times the speed when using nuclear weapons compared with conventional support (more than a 100 km a day, compared with about 40 km).[35]

There was a high level of preparedness for the transition to nuclear warfare, as the fronts had launching ramps available and the Soviet units with ammunition followed within the front. The Soviet Union’s vessels normally carried 2–4 torpedoes/missiles with nuclear warheads during patrols and exercises,[36] which we ourselves were able to establish when the U-137 ran aground in the Karlskrona Archipelago on 27 October 1981. In an interview with the political officer from the submarine 25 years later, he told us that they had considered destroying its nuclear torpedoes. In Latvia, they have written a book about all the military installations the Soviet Union left behind when they pulled out.[37] In the chapter on the air bases equipped with stocks of nuclear weapons, they say that they found an instruction for pilots that they should destroy their nuclear weapons if they were at risk of falling into enemy hands. For this purpose, nuclear weapons were equipped with a conventional charge for destruction.[38]

At the beginning, the US regarded nuclear weapons as a resource that could compensate for conventional inferiority. Their possession of these would deter the Soviet Union from war in every sense. A strategy of massive retaliation would take care of that. When the Soviet Union began to develop its own capability, the US aimed its weapons at the known land-based systems. The Cuban Crisis of October 1962 made the US realise that this was not the answer to every attempt by the Soviet Union to move its positions forward. It was not reasonable for every hostile action to result in nuclear war, a conclusion that led to the ‘Flexible Response’ strategy. They would respond using the military force required in the situation. This led to discussions lasting many years with their European allies, which is why it took time to change. The strategy of Flexible Response was not implemented within NATO until the beginning of the 1970s.

The Europeans would have felt safer with the old strategy. With this new one, there were several questions that had to be resolved. For example, in which situation in the event of a European war would nuclear weapons be used? If the Soviet Union began to cross the Rhine? How would they be deployed? Against the troops at the Rhine, against a later echelon at the river crossings in the Soviet Union or Poland, or as a statement in the Baltic Sea, e.g., against the Baltic Fleet or as a high-altitude nuclear detonation? How would the decision be made? (The answer is that a collective decision-making procedure was developed within the alliance.) There were many questions they had not needed to answer earlier about massive retaliation. The discussions also led, from 1976, to them emphasising that what was important was to be able to defend themselves by conventional means and strengthening this capability.

In the Warsaw Pact things initially moved quicker. As early as 1965, a directive was issued that they would also carry out exercises in conventional warfare. The Warsaw Pact also conducted exercises under different premises. The ‘October Storm’ exercise in 1965 began with a conventional phase, while the ‘Vltava’ exercise of 1966 included nuclear weapons right from the start. In the 1980s, a secret book on general tactics for conventional warfare was still being distributed, but it also talked about the risk of escalation.[39] It was, however, not until 1974 that the Politburo decided that they would not be the first to use nuclear weapons. This was not, however, declared openly until 1984.[40] Decisions within the Warsaw Pact were facilitated by the fact that the balance of power with regard to conventional forces in Europe gradually improved in favour of the Pact. During most of the 1960s and 1970s, it is likely that the Soviet Union believed it could win a conventional war in Europe.

In the middle of the 1970s, the General Staff Academy was teaching non-Soviet participants that NATO was always the party starting the war. This could start in one of the following ways:

- A surprise strike with all-out use of nuclear weapons;

- An attack, initially with limited use but later with all-out use of nuclear weapons

- An attack by the forces in the TSMA without the use of nuclear weapons, i.e., a local war;

- The beginning of war through the gradual escalation of a local war.[41]

The assumptions prior to the Warsaw Pact exercises also had NATO as the attacking party. In actual fact, as the reader already knows, the Soviet Union had adopted a pre-emptive strategy and particularly in the case of nuclear warfare, i.e., when the intelligence services interpreted events within NATO as preparations for an imminent nuclear attack, the Soviet Union would pre-empt this at any cost. There was, of course, a risk involved in taking this view. The intelligence services could overinterpret what was happening. Was there a different view in Washington? The Warsaw Pact exercises carried out, as reported by Germany upon reunification, therefore, created, with their scenarios, an unpleasant feeling, as they assumed, in many cases, that NATO intended to escalate to nuclear warfare after a couple of days, something the Soviet Union would attempt to pre-empt by means of a powerful first strike against these preparations and as support for its offensive right to the Atlantic.

At the end of the 1970s, there was a particularly strong feeling that there was a possibility of European nuclear warfare. So-called tactical use was described in a new secret American manual, which probably also reached Moscow. In turn, the Soviet Union deployed a new missile, the SS-20, which, through its longer range than earlier battlefield weapons, was obviously intended for targets in the UK and France. This was followed by NATO’s so-called Twin-Track decision, which meant that, if the Soviet Union did not withdraw the SS-20 by 1983 at the latest, NATO would deploy the ballistic missile, the Pershing II, and cruise missiles with nuclear warheads in Europe, something that also happened later.

The impression that the Soviet Union had its ‘finger on the button’ during the Cold War has later been reinforced by, for example, a couple of interviews in the English version of the Russian newspaper Kommersant in March 2005, in which Lieutenant-General Matvey Burlakov, the commander of the front in the Southwestern TSMA, states that he personally could have made a decision on the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons. In another interview in the same newspaper, the former Stockholm ambassador Oleg Grinevsky says:

Officially the Soviet Union said that it would not be the first one to use its nuclear weapons. However, in reality things were different. At the maneuvers (for example West-83) they war-gamed delivering a preventive blow to the NATO countries in case authentic information on the preparation of a nuclear attack was received. What “authentic information” meant, was not specified anywhere. I do not know when exactly the concept of the first blow was dropped but it did hold out until 1987.

(A former student at the General Staff Academy says that the Soviet Union would regard the indications they interpreted as NATO increasing its military preparations for war as an established outbreak of war, which would justify them striking first.)

Did this then mean that the Soviet Union was prepared to start a nuclear war? No, says Shevchenko:

... The Soviet leaders are convinced that their victory will come as the result of the development of human society. And, if they can accelerate the process through some small limited conventional wars, so much the better. I only know of one case where a nuclear attack has even been discussed, i.e., in 1969 at the time of the Sino-Soviet border negotiations, as China’s nuclear capability did not constitute any real threat.

Despite the Warsaw Pact’s pattern of exercises, we must certainly consider it the case that, from the mid-1960s, both superpowers attempted to avoid actions that could lead to nuclear war. There was, however, a risk of the superpowers ‘triggering’ each other into one. I will return to this later on when I discuss the 1980s under the heading The Period of Uncertainty.

When he looked back at the Cold War a year or so ago, a senior British intelligence officer stated, ‘neither side would allow themselves to believe that the other side was as frightened as they were’.[42] We were all frightened!

The Invasion

According to the Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service’s notes from the seminars with Cheremnikh, Sweden had previously been just as important a target as Finland and Northern Norway. It was the perception of the Soviet Union (in the 1950s, before the era of long-range missiles, we must presume) that Sweden had a special role for the American strategic bombers.[43] If these were to launch an attack into the Soviet Union’s heartland, with Leningrad and the Moscow area as two important targets, they would require the support of attack and fighter aircraft against the air defences in the Baltic, and the limited ranges of these would preferably require being based in Sweden. Was this the reason for the British and American interest in prioritising practical preparations within air activity in their secret co-operation with Sweden? How far did the discussions on the purpose of these practical preparations go, and at which level? The Soviet Union may already have been aware, through the spy Stig Wennerström that some co-operation was taking place with NATO countries, including the US.

In the first edition in 1964 of Military Review, there is an article by an American colonel by the name of Robert P. McQuail entitled ‘Khrushchev’s right flank’, which describes a Soviet operation against the Northwestern TSMA.

Illustration 7. The invasion picture in ‘Khrushchev’s right flank’ (Source: Military Review, no. 1, 1964)

It is not stated in greater detail what his source is, but it is clear that Colonel McQuail has specialised in the study of the Soviet Union, travelled a great deal in the country and been a liaison officer for the commander of the Soviet group in the GDR. The article is very detailed as regards operational axes, the deployment of forces and operational targets, which suggests that it is more than just speculation. This may have its background in planning from the 1940s while Germany still occupied Norway and the Continuation War was going on in Finland.

The plan involves the occupation of Southern Norway, which Cheremnikh believed was unnecessary. On the other hand, this may have been due to the fact that he was appearing in Oslo and was primarily talking about another period, but also the fact that he may not have known anything about planning in the Baltic military district, whose front ought to have been the one with this mission against Southern Sweden and Norway. The landings in the Kvarken Archipelago and the Gulf of Bothnia in Northern Sweden and Finland are, on the other hand, stated by McQuail to be a mission for the Leningrad military district. Among Rzhavin’s locations for reconnaissance by Spetsnaz patrols for landing in the 1970s was, of course, the Bergen-Stavanger area, i.e., in Southern Norway.[44]

I recognise the ‘hand with fingers’, which in the illustration stretches out from the Baltic States towards ports in Sweden, from Malmö in the south to Härnösand in the north, from a picture that existed at the Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service around 1990, but which can no longer be found. In this, there were these ‘fingers pointing’ towards the ports that we became used to seeing receive visits from Soviet intelligence services during the Cold War: on the south coast of Skåne, in Hanö Bay, Norrköping, Oxelösund, Nynäshamn, Gävle and Sundsvall/Härnösand. Among the Soviet operation maps that were found in a store in the Baltic States at the beginning of the 1990s was the map of Norrköping, printed as recently as 1987. This also concurs with how the intelligence service has targeted Swedish ports in a document that was found in a Lithuanian archive.[45]

In the illustration, the direction of attacks in Finland largely concurs with those Ohto Manninen states applied in the 1940s.[46] In this case, how long could this plan have been considered? Yes, in all likelihood up until the new offensive planning from the beginning of the 1960s in any case, when the strategic bombers were, to some extent, replaced by missiles and flying ranges increased. The invasion plan may have been considered even later as an alternative to encirclement if, due to the circumstances, Soviet was also forced into an armed attack against Finland and Sweden. The military geographical factors of significance were largely unchanged during the entire Cold War, with the exception of the fact that the concentration of the naval forces’ efforts was from the 1960s transferred from the Baltic to the Northern Fleet. The fleets’ strategic nuclear missiles were also concentrated here.

Plavins says that he had been involved in operational exercises in both the Leningrad and Baltic military districts as an inspector for the intelligence services on behalf of the central GRU in Moscow. The exercise with Leningrad’s front staff had taken place as late as during the latter half of the 1970s and involved attacks across Finland against Northern Norway and Sweden. As previously mentioned, they were counting on transport movements through Finland without fighting. An exercise with the Baltic Fleet had taken place in 1968 and involved landings in several locations in the southern half of Sweden, i.e., the same pattern as in McQuail’s illustration. In every arrow showing the direction of attack, one regiment would form the vanguard. In total, they would deploy five or six divisions of different types. As regards this exercise, Plavins has, however, previously stated that it was not the current operational plan; however, in 1968, the encirclement plan should have been the current one for a long time. Their exercises may just have been a reserve plan.

The coastal attack on a wide front fitted in with the nuclear age. During the entire Cold War, the Soviet Union believed that it would be possible to carry out landing operations across, in any case, smaller waters,[47] such as to Denmark or over the English Channel and in the Gulf of Bothnia. The Soviet leadership was ready to accept heavy losses.Over the years, we have asked ourselves why the Soviet Union, if indeed they were actually planning for a landing operation against Sweden, did not manufacture more specific tonnage for the attacking fronts. There is one possible explanation. This widespread landing at many locations along our coast bears similarities to the German operations against Norway in April 1940. These were primarily carried out using ordinary warships and merchant vessels, which increases the prospect of defensive deception in the preparations for and commencement of the operation. As we know, the Soviet Union and Germany developed joint operational concepts in the 1920s. In a seminar at the Swedish National Defence College in the spring of 2007 that had two Russian military historians participating with regards the Baltic Fleet’s planning during the 1920s and 1930s, they stated that Soviet political leaders did not like to see money being spent on special warships whose tasks could, instead, be taken care of by merchant or fishing vessels.[48] In the discussion, this concerned minelayers, but could, of course, just as easily have referred to troop carriers. We must not forget that all ships in the Communist state were owned by the State and could be used by the State for whatever purpose it wished. Once civilian ro-ro vessels arrived, these opportunities increased. Hillingsø tells us that the East Germans, for their part, intended to land by means of fishing boats and ferries in their participation in the Coastal Front’s attack on the Danish islands.[49]

In this case too, the outcome would probably have depended on whether the Soviet Union had succeeded in surprising NATO and to what extent the US had enough time and the inclination to assist in our defence. If the Soviet Union began using nuclear weapons and NATO responded to this at an early stage against troop transports, the outcome would probably have been very uncertain. If nuclear weapons were used, the steadfastness of Swedish political leaders would have been the most decisive factor. I will return to this with my views on the usefulness of our invasion defences during the period of encirclement in the concluding discussion.